Small Craft

Late 19th & Early 20th Century British Yachting

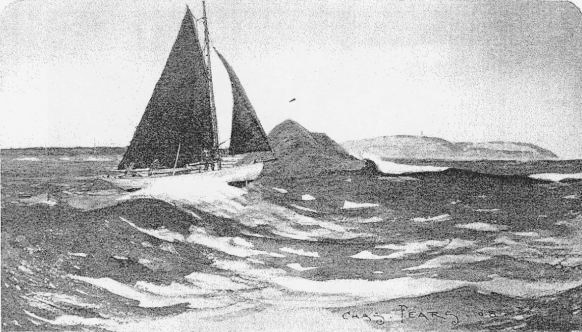

Crossing Orford Bar.

Bringing Home the Mave Rhoe

by Charles Pears

The Yachting & Boating Monthly, 1908

THE Mave Rhoe is a 4-ton spoon-bow counter-stern craft designed by Mr. Flemmich, and built in 1903 by the Teignmouth Yacht and Shipbuilding Company. She had been laid up in a salting at Aldeburgh in 1906 and had remained there until I bought her.

As everyone knows, the water at Aldeburgh is influenced considerably in its rise and fall by the direction and strength of the wind. Thus it was a stroke of luck that the wind shifted to the right quarter when I arrived at Aldeburgh with a friend who henceforth will be known as "Live Ballast."

We at once proceeded to Slaughden and there found just enough water. We hauled off.

As there had been poignant signs of high winds for three days, we were pleasantly surprised the following day to find ourselves gliding down the Ald River in what might have been mistaken for a glorious summer morning. This pleasantry upon the part of the weather helped to annul the annoyance caused by the announcement that the plate had rusted to the keel and would not lower. There, indeed, it remained in spite of repeated heavy blows with a sledge-hammer. Yet, in spite of this and contrary to expectations, she did not make much leeway in the river, though she was dead slow. No doubt the strong tide made her fetch higher than she otherwise would have done.

The rivers Ald and Ore, down which we were skidding, are most interesting; but they cannot be called beautiful, even if Orford village, seen from the river as an oasis in the deserted district, might be classed as very pretty. Thereabouts one passes miles and miles - it impresses one so - of bare shingle and a skyline spiked, to seaward, with hundreds of evenly-spaced telegraph-poles.

We sailed thirteen miles. Nearing the mouth, we noticed the sea was like a duck pond, with just a gentle roller or two breaking upon the bar. Sounding the now boiling, tide-ripped waters of the river with the lead, we ventured out across the ever-shifting bar - I am told the entrance has shifted about half a mile within the last year - a bar which most books of sailing instructions say must not be attempted, without a pilot. Two fathoms, one, two and a half,one and a half. This would do. Up helm and out over it. Heave!. bump! Heave again as the next roller came. Bump! One more heave, and thoughts of the "Galloping Major" were interrupted by the voice of the lead proclaiming us clear and out in the sea. We had to make an offing, and whilst doing this it was so calm that we set the topsail. It was hazy, and we could only just make out the shore half a mile away. Bringing her up to the wind, we could point one point higher than the course to the Gunfleet Head Buoy, which should have been right for tide allowance.

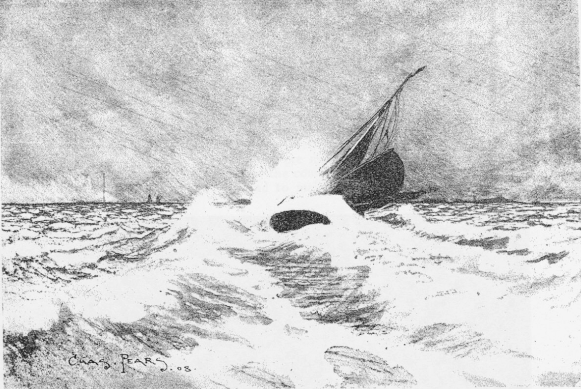

The scourging gale was upon us.

But "the best-laid plans of mice and men," etc. We were soon down to the third reef, with a streaky pink sky over a grey haze that smothered everything.

Straining our eyes for the N.E. Gunfleet Buoy, we heard the faint murmur of a fog-bell.

"That's the Sunk it should be away on the port bow about a mile or so." Squirting along, the bell getting louder and ouder, a ship of sorts gradually hove in sight right ahead.

"Why, that's the Sunk!" I exclaimed. "Good heavens! Two points leeway, hazy, darkness in half an hour, tramps making down Swin. This won't do!" So, bringing her on the port tack, we stood away for Walton, intending to sneak down the shore for Brightlingsea.

It seemed hours that we strained our eyes for the lights of Walton - on - Naze, but suddenly they burst upon us, as did also a very hot squall in which we had to lower the peak. Then the dinghy had to be got alongside and bailed out. No sign of the wind dropping, we decided to run for Harwich.

We guessed the course and bowled along. The dinghy, walking past us, would every now and then be brought up with a jerk and come alongside at the charge. How we cursed the thing!

Yet we saw no lights until the two at Dovercourt came in line, and, as we did not know which side of Landguard Point they were on, we decided to beat up the two lights in line. When we got in a fathom of water we bore away and just sighted the breakwater in time to come about. We bounded along up the harbour.

I knew of no sheltered anchorage except the little pound, and, as I did not fancy that, brought up in the big pound (Felixstowe Dock was out of the question. I had never had occasion to go in, and to "run" into a strange dock is not always advisable). I was just about as dog-tired as I have ever been. I shall never forget the feeling of utter incompetence that came over me as I threw myself down on one of the bunks; I was too tired to sleep.

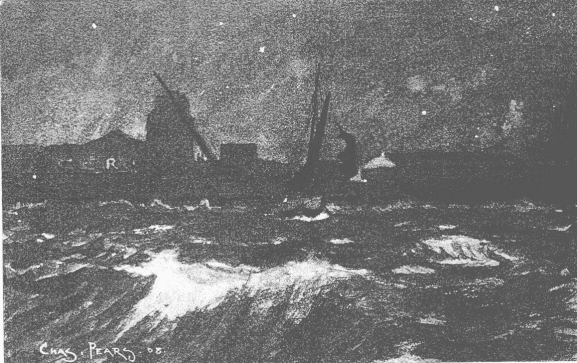

By 4 a.m. the wind had shifted to the north-west and was blowing a gale, and the boat had dragged to within 10yds. of the Railway Pier. No time was to be lost. Up with the mainsail and jib, in with the cable! And so we saved the Mave Rhoe, or rather she saved herself by her ability to claw off without her plate.

Clawing off the Railway Pier at Harwich.

On the following day, however, we started two hours and a half later than we had arranged. The dawn in all its ugliness was just glimmering as we left Harwich. It was clear enough, for one could see the tramps making down the East Swin quite distinctly.

A couple of barges passed us half-way across Dovercourt Bay and soon left us behind. Clearly she wanted that plate for speed more than pointing. We were making to leeward as usual; the barges lay the course right to the Spitway Buoy, whilst we had to make three tacks to fetch.

Across the spitway we picked up the Bell Buoy, alter which a thick mist obscured everything and a hard wind came with it. We hoped to lay the course to the Swin Middle in spite of the tide, but we soaked so badly in the heavy seas that we picked up the N.E. Middle Hook Buoy instead. On coming about on the port tack we decided that if we did not sight the Whitaker Buoy we must run for Brightlingsea.

Glancing astern, we saw the dinghy wallowing badly, and I was just about to haul her in when she took a dive and filled. This thing had been more trouble than it was worth, so we cut her adrift and she went floating away down the East Swin with the ebb, bottom up.

On we sped until once more off Walton, when the wind dropped to that deathlike stillness that precedes a storm. To windward the sky looked awful between the low banks of black clouds another strata was being torn into ribbons. We should soon be in the thick of it. And after rounding the Naze it burst upon us from the N.W., having shifted round from the W. Now, indeed, would our rusty shrouds be tried! The water was like mud, torn, scratched, and flecked with myriads of p~itches of whitest cotton wool. The waves were little, but short and steep, and every now and then one would burst into a cloud of spray at the bows.

The Mave Rhoe staggered rail awash across the bay, the mainsail with the gaff jaws lashed to the gooseneck, the topping-lift taut, and a gasket through the last cringle was just enough to prevent a dangerous amount of lee helm; the jib was doing all the work.

Whiry! the mainsheet whistled out at the slams.

The "Live Ballast," what of him? He, with that passive courage which receives no sustenance from activity, was doing the best thing he could - squeezing his rotund form as far out to windward upon the port bunk as he could get it.

Half an hour saw us, luckily with the stick still in, turning up the Stour. With lowered mainsail we ran round the pier under the jib and caught hold of a steam-tug that was warped alongside.

The excited little crowd that had scampered along the pier on sighting us helped us to make fast. Though quite unnecessary, it was a kindly act, and even the harsh voice of the Harwich imp who announced the obvious fact that we had lost the dinghy seemed a pleasant thing. Next morning the newspaper headlines that first caught our eyes were - "Great Gale - Holyhead Lifeboatmen's Struggle for Life - Part of Southend Pier Carried Away."