Small Craft

Late 19th & Early 20th Century British Yachting

The Sailors: Amateur British & Irish Yachtsmen Before World War One

From Zerixee we once more tried to reach Veere, and once more we were doomed to failure. Alterlie went aground first as we were skirting the island of north Beveland, and before turning into the channel on the left bank of which lies Veere.

A simple method of fishing.

The tide was ebbing, so we couldn't afford such diversions, and as the minutes passed and the two figures leapt and strained to no purpose I thought we were there for good. She got off finally, however, her crew stripping and getting overboard and shoving, while I hovered around, camera in hand, trying to get a photograph.

In the Zuid Vliet channel Alterlie drew ahead, and, becoming careless, I ran full tilt on the mud. This time it was hopeless; shoving availed nothing, not even going overboard, and by the time they had come back Mave-Rhoe was lying right over. And so once more we were compelled to give up any idea of Veere as a night's anchorage, and lay on the sea wall in the sun and the wind, watching the white sails on the Englische Vaerwater. In the evening, with the first of the ebb, we got under way again, but the wind fell light, and dusk came before we had reached Kortgene. To attempt to thread the channel in the dark was, we knew, hopeless, for it is not lighted, and winds in all directions.

In the Zuid Vliet channel Alterlie drew ahead, and, becoming careless, I ran full tilt on the mud. This time it was hopeless; shoving availed nothing, not even going overboard, and by the time they had come back Mave-Rhoe was lying right over. And so once more we were compelled to give up any idea of Veere as a night's anchorage, and lay on the sea wall in the sun and the wind, watching the white sails on the Englische Vaerwater. In the evening, with the first of the ebb, we got under way again, but the wind fell light, and dusk came before we had reached Kortgene. To attempt to thread the channel in the dark was, we knew, hopeless, for it is not lighted, and winds in all directions.

In the evening we got under way, but the tide was still flooding, and we made but little progress. It was rather galling that as the tide slackened and began to ebb the night fell, and by the time we were off Kortgene it was dark. It was just before we brought up that we were tackled by the police boat on the subject of a masthead light. How we managed it or how they managed it I do not know, but we did in some sort of way carry on a conversation. Alterlie was rightfully indignant, I think, that her red and green lights should have to be displaced by a common white light; but I had no defense whatever, my tricolour not even being at that moment alight.

We had meant to have a few hours' sleep and then take the last of the ebb down to Veere, but to our mutual regret the boats were swinging when we woke, and we had to make our passage against the flood. We had the same rather tedious crawl through the canal from Veere to Middleburg, towing along the bank the greater part of the way. At Middleburg Oswald left us to take the train to Flushing, where he expected a letter that either granted him another week's leave or a summons to return to England by that night's boat, and having taken a stock of tobacco and cigars we too toiled on to Flushing. After a strenuous day that had lasted from five in the morning to seven in the evening and two nights with very broken rest, William and I felt the need of a dinner on shore, and while we were toying with the idea Oswald arrived, bursting with his extension of leave and just such a dinner as we had been dreaming of.

We had meant to have a few hours' sleep and then take the last of the ebb down to Veere, but to our mutual regret the boats were swinging when we woke, and we had to make our passage against the flood. We had the same rather tedious crawl through the canal from Veere to Middleburg, towing along the bank the greater part of the way. At Middleburg Oswald left us to take the train to Flushing, where he expected a letter that either granted him another week's leave or a summons to return to England by that night's boat, and having taken a stock of tobacco and cigars we too toiled on to Flushing. After a strenuous day that had lasted from five in the morning to seven in the evening and two nights with very broken rest, William and I felt the need of a dinner on shore, and while we were toying with the idea Oswald arrived, bursting with his extension of leave and just such a dinner as we had been dreaming of.

At Middleburg Market.

So off we set, William and I, while Oswald looked after the boats. We lost ourselves continually, for no one we met had any English, but finally we did happen on a man that guided us to the hotel where Oswald had dined so sumptuously. We were not disappointed. The dinner will live in my memory always. Both ravenous with hunger and thirsty as only those who have toiled all day in the sun can be, we filled in the quarter of an hour while we waited for dinner with deep draughts of wine. Drinking on an empty stomach (and how empty our stomachs were!) produced the usual result, and by the time the soup appeared we were smiling blandly at one another, and speaking with that slow deliberate earnestness that betokens men not quite sober. Our table was set by the open window, and before us passed a continual stream of laughing, talking people. We smiled at them, we smiled at one another, we smiled at the waiter, and between the courses we went fast asleep. I remember no topic of conversation--I daresay there was none--but to this day I can see William's solemn face and blinking eyes as he struggled to concentrate his attention on some fatuous remark of mine, and then abandoned himself to inconsequent smiling.

How we ever got ourselves away from that pleasant dinner table I do not know, but we did eventually, and strolled homewards through the old part of town. Every now and then, on account of the unevenness of the cobbled streets, no doubt, we would lurch ever so slightly against one another, and beg one another's pardon, and smile and beam and try to say "not-at-all" in one syllable. From time to time William (who is an architect) would become almost maudlin about some doorway or molding that appealed to his aesthetic sense. In the inner basin were lying two of the Antwerp pilot boats, most noble vessels, that would make for the man who has a taste for real cruising almost ideal yachts. I have a hazy memory of how we fell admiring them, their size, and their headroom, and how pitiful it struck us that such fine fellows as ourselves, men of taste and sensibility, should have to crawl about in insignificant three-tonners. And so finally we got back again to our boats, and having applauded Oswald at some length on his acumen in having found such a hotel, we turned in.

The next morning we locked out of the canal, crossed the Scheldt, and set off down the coast. We had a fair wind, and had intended to push along to Nieuport or possibly Dunkirk, but when we were off Ostend the wind fell light, and we decided to put in there for the night and make straight for Ramsgate in the morning. Incidentally I was rather glad to see Ostend. The harbour is, to my way of thinking, distinctly good. One can lie at one's anchor up near the yacht club, and therefore is saved that messy business of warping. In August, perhaps, the anchorage is more crowded, but this was July, and we had plenty of room. After dinner we went to have a look at the town. Oswald and I had condescended to collars and ties and shore clothes, but William scorned any such weakness. In an old tweed hat several sizes too small for him, with moreover a large hole burnt in the top, a three days' beard, an arsenic green muffler, and a flannel suit whose trousers ended considerably above his ankles, he gave one somehow the impression of a simple countryman who finds himself exposed for the first time to the garish brilliance of a town. He was lethargic, too, a lethargy that lager beer seemed but to deepen, and it was plain that whatever spell Ostend might have for others he was immune from. A foolish place indeed it seemed to all of us, and the season not having yet begun there was a dead-alive air about it that was rather depressing. Many hotels were shut, many but half-filled, and everywhere one met parties of one's countrymen obviously rather impressed that they were at Ostend, and determined to act up, at least in manner, to the traditions of the place.

How we ever got ourselves away from that pleasant dinner table I do not know, but we did eventually, and strolled homewards through the old part of town. Every now and then, on account of the unevenness of the cobbled streets, no doubt, we would lurch ever so slightly against one another, and beg one another's pardon, and smile and beam and try to say "not-at-all" in one syllable. From time to time William (who is an architect) would become almost maudlin about some doorway or molding that appealed to his aesthetic sense. In the inner basin were lying two of the Antwerp pilot boats, most noble vessels, that would make for the man who has a taste for real cruising almost ideal yachts. I have a hazy memory of how we fell admiring them, their size, and their headroom, and how pitiful it struck us that such fine fellows as ourselves, men of taste and sensibility, should have to crawl about in insignificant three-tonners. And so finally we got back again to our boats, and having applauded Oswald at some length on his acumen in having found such a hotel, we turned in.

The next morning we locked out of the canal, crossed the Scheldt, and set off down the coast. We had a fair wind, and had intended to push along to Nieuport or possibly Dunkirk, but when we were off Ostend the wind fell light, and we decided to put in there for the night and make straight for Ramsgate in the morning. Incidentally I was rather glad to see Ostend. The harbour is, to my way of thinking, distinctly good. One can lie at one's anchor up near the yacht club, and therefore is saved that messy business of warping. In August, perhaps, the anchorage is more crowded, but this was July, and we had plenty of room. After dinner we went to have a look at the town. Oswald and I had condescended to collars and ties and shore clothes, but William scorned any such weakness. In an old tweed hat several sizes too small for him, with moreover a large hole burnt in the top, a three days' beard, an arsenic green muffler, and a flannel suit whose trousers ended considerably above his ankles, he gave one somehow the impression of a simple countryman who finds himself exposed for the first time to the garish brilliance of a town. He was lethargic, too, a lethargy that lager beer seemed but to deepen, and it was plain that whatever spell Ostend might have for others he was immune from. A foolish place indeed it seemed to all of us, and the season not having yet begun there was a dead-alive air about it that was rather depressing. Many hotels were shut, many but half-filled, and everywhere one met parties of one's countrymen obviously rather impressed that they were at Ostend, and determined to act up, at least in manner, to the traditions of the place.

Life at Ostend - as we expected to find it - ... And!

William, more hostile than ever, had thoughts for nothing but stores, a matter which we left until too late, having in the end to be content with some eggs and cheese purchased from a smelly little shop in a back street. And finally, we discovered that the last tram had gone (it was only eleven), and we had to walk a weary mile back to the boats.

The next morning was misty, with promise of great heat, but at least had every appearance of remaining fine for our passage. And at about 8 o'clock we got under way. As we slipped out of the harbour mouth, the fishing fleet came blundering in, heavy ketches most of them, and we were glad to get into open water. The breeze was on our beam at first, but came more and more aft, until eventually we could again set spinnakers. Oswald was sailing with me for today, and we fixed up a blanket over the deck to serve as an awning, while William on Alterlie steered under his umbrella. It always had a grotesque effect, this umbrella, more especially on the open sea, but there was no doubt that it was a useful thing to carry.

We could not see Nieuport Bank buoy, but our charts were old ones, while the compass course could not fail us. It always strikes me at sea in hazy summer weather that one thinks that one can see a great deal further than is actually the case. The true horizon is veiled in haze, without seeming to be, and often one's vision ends at three miles or so, while the sea appears to extend perhaps four times that distance. A rather curious feature of this particular passage was that we were visited (when some twenty miles from land) by a perfect plague of insects. Butterflies, gnats, all kinds of flying beetles dropped on our decks and invaded the cabin in swarms. Perhaps some naturalist reader could tell me if this is a common occurrence.

The next morning was misty, with promise of great heat, but at least had every appearance of remaining fine for our passage. And at about 8 o'clock we got under way. As we slipped out of the harbour mouth, the fishing fleet came blundering in, heavy ketches most of them, and we were glad to get into open water. The breeze was on our beam at first, but came more and more aft, until eventually we could again set spinnakers. Oswald was sailing with me for today, and we fixed up a blanket over the deck to serve as an awning, while William on Alterlie steered under his umbrella. It always had a grotesque effect, this umbrella, more especially on the open sea, but there was no doubt that it was a useful thing to carry.

We could not see Nieuport Bank buoy, but our charts were old ones, while the compass course could not fail us. It always strikes me at sea in hazy summer weather that one thinks that one can see a great deal further than is actually the case. The true horizon is veiled in haze, without seeming to be, and often one's vision ends at three miles or so, while the sea appears to extend perhaps four times that distance. A rather curious feature of this particular passage was that we were visited (when some twenty miles from land) by a perfect plague of insects. Butterflies, gnats, all kinds of flying beetles dropped on our decks and invaded the cabin in swarms. Perhaps some naturalist reader could tell me if this is a common occurrence.

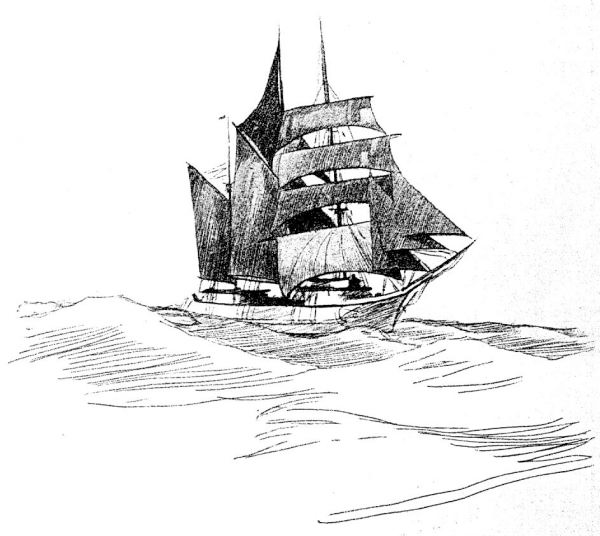

Off the Sandettie.

In the afternoon Oswald left me to relieve William at his helm. We should have made out the Sandettie, but in the haze it was invisible, and we should see nothing now until we made our landfall. At about sunset I thought I could make out the Foreland, and as dusk came we could see the Foreland light. Soon after the breeze changed suddenly to the sou'west, bringing it on our beam, and I had a busy five minutes with the spinnaker; then later it headed us and died away to almost nothing. Evidently the mist had come down again, for the Foreland light was invisible; our hope of getting into Ramsgate that night vanished, and the prospect of a night at the tiller became a certainty. It was a tedious business; so little breeze was there that I could scarce keep way on Mave-Rhoe, and she was foul. In the swell we rolled about in the usual lifeless fashion, and the only indication of our position was a far distant groaning, which we recognised to be the Mouse. With two on board and plenty of food one would have accepted the position calmly enough, but alone, and with only one day's food ahead, there was just enough anxiety in the position to keep one at the tiller trying to get along.

As the dawn came I hoped to see the land, but the grey half light broadened and broadened, and still one could see nothing. One consolation there was, that the breeze had freshened, and we were slipping through the water at a tolerable pace. As we kept plodding along, making long boards, there came upon me the most intolerable sleepiness. Except for Alterlie--who looked ridiculously small and lost--there was not a sail in sight. The sea and the sky alike were grey, the blank horizon seemed on all sides infinitely far away, and after the chill waste of waters, Mave-Rhoe's cabin looked marvelously homely and comfortable. From where I was steering I could see my bunk, with its cushions and unused blankets, and my sleepiness became gradually overmastering. I weakly told myself that I would let Mave-Rhoe sail herself for three minutes and have a rest. In three minutes I was fast asleep, and the next thing I knew was that Alterlie was alongside shouting at me to get up. Oh, the blinking stupor of those first few minutes in the cold air again! still dazed with sleep, and still no sight of the Foreland. William came over in the dinghy and we conferred. I had to own myself lost, but he was sure that we could not be far out of our course, the only question being which tack should we lie over on. He entered into minute reasons for our being where he thought we were, and in the midst of them I was overwhelmed with furtive laughter at the memory of a drawing of Mr. Briscoe's in which two, rabbit-faced yachtsmen were are poring over a chart. Their skipper is despondent. "If we're anywhere I think we are," he says, "and I don't think we are--we're somewhere about here," and he covers about a hundred square miles of the North Sea with his hand.

As we talked a little sadly we observed Oswald, who had binoculars, gesticulating wildly and pointing. We stared ahead anxiously--and understood. The Foreland was just showing itself through the haze, some five miles away. Not until we saw it did I realise how lost I had felt, and it was extraordinary what a relief it was to know that one was steering in the right direction, instead of only hoping it. We had evidently drifted out of our course in the night, and, had we lain over on the other tack, should in all probability got in sight of the Mouse before we knew where we were.

Quite a pleasant breeze sprang up as the sun rose, and we could lie comfortably for the Foreland, our intention being to bring up under it, and wait for the ebb that should take us to the Whittaker Beacon and so to Burnham. Our resolution weakened as we got close in shore, however, for there was a most uncomfortable roll, and finally we abandoned the idea of getting home that day, and went into Ramsgate. We moored in our old berth, and in a few minutes had our red ensigns fluttering in the breeze. At least Alterlie's fluttered, but Mave-Rhoe's being very small and apparently made of some gauzy material, stood stiffly out, motionless like a ballet dancer's skirt. Still, there it was, a signal that His Majesty's Customs durst not ignore, and presently they appeared in the person of a cynical dark man in a colossal boat. He managed to keep a straight face on Alterlie, but the sight of that tangled bit of finery at my masthead was too much for him, and with a subtle humour that I was at a loss to understand he asked me if I had any dogs on board.

I shall never forget the heat of that day in Ramsgate. As if we were not already stupid with lack of sleep, we must go and eat a colossal lunch. William, as usual, was the sleepiest. He kept dropping his knife and fork alternately and then waking up with a start and apologising. Our evening in Flushing was like an attack of insomnia by comparison. After lunch we sat in the cool hotel lounge and blinked at one another until William again went fast asleep on a plush covered lounge. Near him was one of those infernal machines which, on being fed with a penny, will create enough uproar to wake the dead. 'Orchestrions' I believe they are called. We put a coin in, hoping to galvanise him into life, but he only wagged his head dreamily in tune and did not wake. Upstairs some kind of a meeting was going on, and its members had left their hats in the lounge, so the orchestrion having failed us, Oswald and I amused ourselves by delicately placing them one above the other on William's head, and I shall never to my dying day forget the sight of that sleeping Scottish gentleman at one time crowned by no fewer than six hats. The exquisite humour of the situation lay in the fact that the casual stranger entering the lounge was confronted by the pitiable sight of a young and handsome man sunk deep in drunken slumber, wearing six hats. And when the dignified barmaid saw him we had to stuff our handkerchiefs into our mouths and clutch one another. We got him away at last, and turned in early, glad yet sorry to have got back to England.

Our passage to Burnham the next day was uneventful enough, and once more on our moorings our cruise was over. Over in one sense that is, but in another it will never end, and long after Alterlie and Mave-Rhoe have made their last cruise together and William and Oswald and I are quavering, toothless old gentlemen, we shall paddle around to one another's houses and continue it on winter evenings by the fire.

As the dawn came I hoped to see the land, but the grey half light broadened and broadened, and still one could see nothing. One consolation there was, that the breeze had freshened, and we were slipping through the water at a tolerable pace. As we kept plodding along, making long boards, there came upon me the most intolerable sleepiness. Except for Alterlie--who looked ridiculously small and lost--there was not a sail in sight. The sea and the sky alike were grey, the blank horizon seemed on all sides infinitely far away, and after the chill waste of waters, Mave-Rhoe's cabin looked marvelously homely and comfortable. From where I was steering I could see my bunk, with its cushions and unused blankets, and my sleepiness became gradually overmastering. I weakly told myself that I would let Mave-Rhoe sail herself for three minutes and have a rest. In three minutes I was fast asleep, and the next thing I knew was that Alterlie was alongside shouting at me to get up. Oh, the blinking stupor of those first few minutes in the cold air again! still dazed with sleep, and still no sight of the Foreland. William came over in the dinghy and we conferred. I had to own myself lost, but he was sure that we could not be far out of our course, the only question being which tack should we lie over on. He entered into minute reasons for our being where he thought we were, and in the midst of them I was overwhelmed with furtive laughter at the memory of a drawing of Mr. Briscoe's in which two, rabbit-faced yachtsmen were are poring over a chart. Their skipper is despondent. "If we're anywhere I think we are," he says, "and I don't think we are--we're somewhere about here," and he covers about a hundred square miles of the North Sea with his hand.

As we talked a little sadly we observed Oswald, who had binoculars, gesticulating wildly and pointing. We stared ahead anxiously--and understood. The Foreland was just showing itself through the haze, some five miles away. Not until we saw it did I realise how lost I had felt, and it was extraordinary what a relief it was to know that one was steering in the right direction, instead of only hoping it. We had evidently drifted out of our course in the night, and, had we lain over on the other tack, should in all probability got in sight of the Mouse before we knew where we were.

Quite a pleasant breeze sprang up as the sun rose, and we could lie comfortably for the Foreland, our intention being to bring up under it, and wait for the ebb that should take us to the Whittaker Beacon and so to Burnham. Our resolution weakened as we got close in shore, however, for there was a most uncomfortable roll, and finally we abandoned the idea of getting home that day, and went into Ramsgate. We moored in our old berth, and in a few minutes had our red ensigns fluttering in the breeze. At least Alterlie's fluttered, but Mave-Rhoe's being very small and apparently made of some gauzy material, stood stiffly out, motionless like a ballet dancer's skirt. Still, there it was, a signal that His Majesty's Customs durst not ignore, and presently they appeared in the person of a cynical dark man in a colossal boat. He managed to keep a straight face on Alterlie, but the sight of that tangled bit of finery at my masthead was too much for him, and with a subtle humour that I was at a loss to understand he asked me if I had any dogs on board.

I shall never forget the heat of that day in Ramsgate. As if we were not already stupid with lack of sleep, we must go and eat a colossal lunch. William, as usual, was the sleepiest. He kept dropping his knife and fork alternately and then waking up with a start and apologising. Our evening in Flushing was like an attack of insomnia by comparison. After lunch we sat in the cool hotel lounge and blinked at one another until William again went fast asleep on a plush covered lounge. Near him was one of those infernal machines which, on being fed with a penny, will create enough uproar to wake the dead. 'Orchestrions' I believe they are called. We put a coin in, hoping to galvanise him into life, but he only wagged his head dreamily in tune and did not wake. Upstairs some kind of a meeting was going on, and its members had left their hats in the lounge, so the orchestrion having failed us, Oswald and I amused ourselves by delicately placing them one above the other on William's head, and I shall never to my dying day forget the sight of that sleeping Scottish gentleman at one time crowned by no fewer than six hats. The exquisite humour of the situation lay in the fact that the casual stranger entering the lounge was confronted by the pitiable sight of a young and handsome man sunk deep in drunken slumber, wearing six hats. And when the dignified barmaid saw him we had to stuff our handkerchiefs into our mouths and clutch one another. We got him away at last, and turned in early, glad yet sorry to have got back to England.

Our passage to Burnham the next day was uneventful enough, and once more on our moorings our cruise was over. Over in one sense that is, but in another it will never end, and long after Alterlie and Mave-Rhoe have made their last cruise together and William and Oswald and I are quavering, toothless old gentlemen, we shall paddle around to one another's houses and continue it on winter evenings by the fire.