Small Craft

Late 19th & Early 20th Century British Yachting

The Sailors: Amateur British & Irish Yachtsmen Before World War One

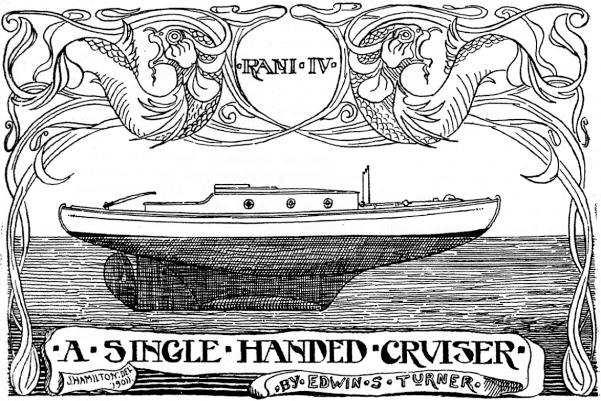

SHE followed a line of sisters whose name was already of honourable repute; for which reason, perhaps, she was christened Rani IV. As her first owner explained, when he designed her he aimed at producing a boat which, being first and above all seaworthy, should also have as much cabin space as possible on a very light displacement. To this end she was given a fin keel and bulb, and her afterbody was carried out in a sharp canoe-stern; this, coupled with a moderate fin, being, in her designer's experience, the best type for a small seagoing boat.

Her overhangs were moderate, with the forward sections as sharp as might be, so that she should not "spank" as most fin-keelers do. Aft, the overhang was kept low to secure the buoyancy of the canoe-stern, and full sailing length when heeled. She was built of teak, oak, and elm; with steamed timbers and pine planking. Rigged as a stemhead sloop, with roller reeling-gear to both sails, and pull-round foresail, her principal dimensions were

L. 0. A., 26ft.

L. W. L., 20ft.

Beam (extreme), 6ft.

Beam (at W.L.) 5ft. l0ins.

Depth, 3ft. l0ins.

Overhangs (each), 3ft.

Max. depth of hull, ift. 8ins. W.L., to garboard.

Weight of fin, 3 cwt.

Weight of bulb, 15 cwt.

Total displacement, 4,095 lbs.

Length of cabin, 8ft.

Bunks, 8ft. by 2ft. to 1ft. 4ins.

Width of cabin floor, 1ft. 8ins. to 1ft. 2ins.

Well, 4ft. 4ins. by 4ft. 9ins.

Width of cabin top, 4ft. to 4ft. 9ins.

Headroom, 4ft. 4ins.

Rani amply justified her designer's ideas, proving herself also to have a good turn of speed. But she carried considerable weather helm, and griped so much in strong winds that a bowsprit and jib were added to balance her.

After a season or two she came into the hands of one who, sailing her hard and often, began to improve her. Under her new rig she carried overmuch sail for comfort in open water, so the bowsprit and jib were removed and the mainsail reduced. Having still a tendency towards weather-helm, a piece was added to the after end of the fin and the rudder rehung. It had originally worked through a vertical tube about two feet abaft the end of the fin; but on the latter being lengthened, the tube was given a slight rake and the heel of the rudder pivoted to the fin.

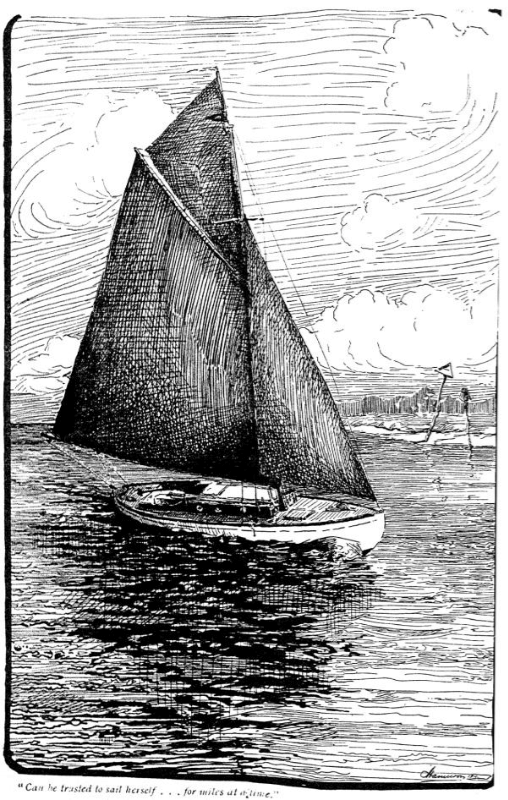

The result was a complete success. The boat steered with a couple of fingers in any weather, and has since been so nicely balanced that when making passages in anything but dead-light airs, or with the wind right aft, she can be trusted to sail herself, with an occasional touch of the tiller, for miles at a time.

The well, being considered too large and open for a long sea-passage in prospect, was made watertight. It was not self-emptying, because in a small boat when heeled the lee corner of the floor comes at once below the water-line. But the floor was raised, and reduced in area by bulkheading off a broad seat across the cabin entrance. All locker doors were faced with rubber, and set up tight with thumbscrews. As a matter of fact these precautions have never been necessary, because the boat's buoyancy is such that no sea has yet found its way into the well in serious quantity. But that they were efficient was proved when she was taken to sea on a bad day, hove-to, and the cockpit filled up by hand to see what would happen. In the result, directly she began to lie over and sail again she forthwith threw all the water out to leeward, except a bucketful or two, which could safely be allowed to run into the bilge by the lifting of a plug, and cleared thence with the pump.

As to the pump itself, it was one of the ordinary deck-suction type; well enough on an even keel, but not to be worked effectively when it might be needed most. A horizontal lever handle was therefore added, shipping into a rowlock-hole on the cockpit coaming, and long enough to be reached easily from the tiller. No link-motion was needed; the play in the plunger-rod being sufficient.

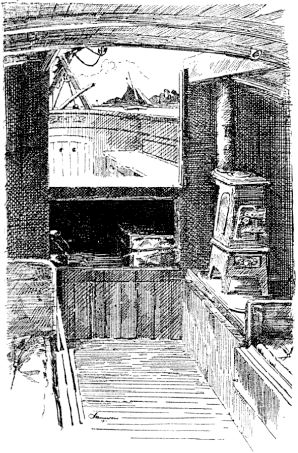

Another great improvement under that owner was the coal stove. He wanted to sail in the winter, but his acquaintance for the most part scoffed at the idea of putting such a thing into a sightly little canoe-yacht. I however, being sympathetic, was invited to discuss the point. It seemed to me that there was but one place where the stove - the smallest sized "Bogie" - could happily go; and that was at the after end of the port settee, which, being eight feet long, might just as well be six; the funnel being led through the corner of the cabin-top, and continued horizontally outside to clear the boom. And I said so, little thinking that I should ever reap the harvest of my own advice. But so it befell, for there came a day when Rani passed into my keeping.

During what remained of our first summer together, I sailed her as she was. I had always had an affection for the little lady. I had watched her for more than one season, and had seen her in fair weather and in foul, bobbing about in the North Sea, fifty miles from any land, wriggling up narrow creeks, and once, half-hidden in spray, beating up, hard driven for safety. So, knowing she was worthy, I had taken her, not as a light love, but to have and to hold, and there was no need to hurry. Moreover, it seemed prudent to hasten slowly when trying to improve on that which had sufficed at least two good men before me. It did not take long to find that there was small room for betterment on deck, except in details. Every trip showed afresh how carefully things had been thought out. The mainboom gooseneck pleased me. Instead, of the usual single mast-band, and a knuckle-joint which has to carry a heavy shearing strain and is liable to bend, the thrust of the boom was taken by two bands, with the gooseneck working between them on a vertical pin. Also, instead of gaff-jaws and parrels, there was a broad brass collar, leathered, and going right round the mast with nothing to foul or get loose. The anchor stock housed into a tube alongside the mast, so that the palms could lie flat on deck.

The roller foresail I speedily discarded finding it was seldom needed. Apart from the extra weight aloft, which is in itself a serious drawback in a small boat, I have a feeling that the less machinery there is about a singlehanded cruiser's gear the safer for him. So I have used ever since a sail hanked on to the stay and hoisted from the well. The risk of mishap is reduced to a minimum because there is nothing to go wrong, and in practice it rarely happens that the sail cannot be got cleanly out of the way before bringing up to an anchor or mooring. It is true that the absence of a rolling sail calls for a change of jibs when the second reef goes into the mainsail; but as the canvas is small and the boat stands well up to it, this is not of noticeably frequent occurrence. At such times, however, the weather is generally fairly bad, and when in open water one has no spare fingers to play with shackles and pins, or with mousings; so that on head and tack I use strong snap-shackles, which can be fixed or cast adrift safely in a moment with one hand.

But as any kind of shackle is dangerous on a flapping foresheet, I have there a wooden toggle and grommet of raw hide (so-called); a most reliable fitting, which never shakes adrift, and can be handled easily, however cold or wet one's fingers may be. This "raw hide," procurable in 6ft. strips under the name of "Helvetia" belt-lacing, is excellent stuff to have aboard. It comes in for many purposes where rope would chafe, is extraordinarily strong, and does not harden.

Rani's waterways being narrow, her spare spars lay unhandily thereon, being, besides, a source of danger underfoot. So I had a pair of "Y"-shaped "lumber irons" made, large enough to take them all, and socketed to each end of the cabin coaming, so that the spars could lie in them, fore and aft, tidy and out of the way. This is a dodge that I can recommend to brethren in small vessels. For a cruiser, the extra top-weight and wind-age are theoretical and not appreciable and even if they were, would be paid for in convenience gained.

I took a very early opportunity to make a clean sweep of all manilla running-gear in a boat, in favour of Italian hemp with a slight touch of tar in it - beautiful stuff, which never snarls or thickens, wears indefinitely, is stronger than manilla, and does not stretch. Save for this, and the foresail, I made no alterations when she had a new mast and rigging. Everything led comfortably to hand in the well, and nothing could be improved; so I left the halliards as I found them: single whips of wire, with tail-blocks, through which rope falls led aft to cleats on the cabin-top.

Some decry thin flexible wire for halliards, on the ground that it is apt to corrode insidiously and "go" suddenly. Personally, I have always found that a wire rope gives due warning before it goes, and if it is kept well oiled, it lasts for years. Oil, by the way, is a thing sadly stinted aboard the average boat. A mere bicycle - and kept under cover withal - gets a drink of oil all round before a long run; but a poor little cruiser, out in all weathers and subject to all sorts of strains, is expected to carry on year in and year out with never a drop to ease her. It pays, in hard cash saved and in freedom from accident, to start every cruise with an oil-can, and to keep on using it.

When the time came for a new mainsail, I was sorely tempted to revert to the rolling boom-gear which my immediate predecessor had discarded, but in the end I stuck to earings and tackles, and have so far been spared cause for regret. In my case there was the feeling, "Better the devil you know than the devil you don't." The boat went very well as she was; balanced perfectly, and even with a loose-footed mainsail would lie well within four points. It may seem somewhat heretical to say so, but I believe that a man singlehanded in a really handy cruiser of, say, four or five tons, is just as well off without patent reefing gear; that is to say, the potential risk of something going wrong is not worth the time saved. So long as nothing does go wrong, rolling gear is admirable; especially when the mainsheet can be worked from the boom-end. But when the boom is so long as to need a claw-ring, an element of danger is introduced, because the buttons on the ring undoubtedly chafe the sail, and may tear it if they break, as they often do. Moreover, when rolling up alone in rough weather, there is always a possibility of the ring getting foul in the sail; and in a heavy gybe the whole boom has been known to jump clean off the gooseneck. In theory these things ought not to happen, but in practice they sometimes do, even with the greatest care; perhaps not once in a score of trips, but it is just that "once" which is unsafe to chance singlehanded.

On the other hand, a rope earing and tackle may be comparatively slow; but they are sure, and no trouble to haul down when the gear is light enough to be well under control. Cruising is not racing; a few extra minutes make no difference on a passage, and once a well-oiled earing is home and the points tied, nothing can go wrong. By putting a double block on the boom instead of the usual single one, the fall of the reef-tackle can be made to lead aft into the well instead of along the deck, so that the earing can be got down without leaving the helm; also, one can, if necessary, get out to the boom end and settle the sail with one hand whilst pulling the purchase in with the other.

It is generally a difficult matter to keep a compass free from deviation in a small boat. In Rani's case the problem was complicated by the fact that the water-tank, coal stove and cooking-gear made considerable iron close to the after end of the cabin. After some experiment, the difficulty was overcome by fixing to the broad seat across the cabin entrance a stout detachable teak upright, shipping into a socket on the well floor, and held rigid with a strong brass bolt and wing-nut. On this upright the compass was hung; almost in the middle of the well, close to the helm, giving clear room all round it, and access to the cabin, free from deviation and convenient for taking bearings all round the horizon. The whole fitting can be put up or taken down in a few seconds, and the idea is one which, from experience, I can recommend. In cases where the companion leads directly from the well, a strong pillar, passing through a hole in the floor and socketing into the keelson, suggests itself.

The problem how to go to sea in full marching order, yet preserving the maximum of living-space, was simple enough in theory, one had merely to apply the principle, "A place for everything, everything in its place, and the least-wanted things in the furthest corners," but in practice its simplicity was overlaid by considerations of expediency, weight and trim; of which the two latter are of vital importance in a small, light boat.

So here again, though the main idea crystallised almost at once, I waited to see if it would stand the test of time and practice. A mistake is easier made than mended, and a plugged screw-hole is an eyesore for ever.

Nevertheless, there was one little fitment about which there could be no chance of a mistake - bunk-boards, good high ones. In they went at once, treble-hinged to each settee. I had had them in every previous boat, and did not feel safely tucked up in bed without them. It has always been a mystery to me why every little cruiser is not fitted with bunk-boards. They take up no room, but make a vast difference to one's comfort, and are equal to an extra blanket for warmth. They should have not less than three brass-pinned hinges apiece, and care should be taken to make the hooks, or bolts, that hold them up, amply strong.

For eight good feet beyond the mast the boat was completely empty. In times when I had been a passenger aboard, it had always seemed to me that blanket bags, portmanteaux, spars, and sails, had lived there at random - the most wanted article generally at the bottom, or in the chain-bin - simply for lack of economical lockering and shelving. In justice to the previous owners it must be admitted that the long nose of a shallow-bodied boat is hard to get at, and heavy weights must not be stowed there. But it is just the shape to take light and bulky articles which are not constantly in use - blankets, and spare clothes, to wit.

So in went a four-foot shelf, and abaft it a single big locker was bulkheaded off, half the width of the boat and three-and-a-half ft. deep. A curtain divided this locker from the cabin, and except for a single shelf and raised floor there were no divisions. Pigeon-hole lockers are wastes of space, dark, harbour dirt, and are not adaptable. Broad, clear shelves, opening either forward or aft, are handier and cleaner. Things can be kept in them in trays or boxes - crockery in one tray, groceries in another, and so on, each species of article together. The trays chock each other off, and can be shifted about to accommodate anything extra bulky. This method of stowage, too, renders the back of a deep locker just as useful as the front, inasmuch as it is only necessary to reach half-way down to lay hold of a tray.

The other side of the boat abreast the mast was left open for access to the hatch and fore-peak. The forehatch was made tight by screwing it down on to felt-covered "draught-excluder" with a thumbscrew and a bar across the underside of the opening. It may be worth noting that I have found the felt-covered "excluder" the only kind with any lasting quality in it. The plain rubber patterns perish in a few weeks.

I record here, for the benefit of anyone similarly troubled, that no sooner had I taken the boat over than I become aware of a strong musty smell, which I eventually traced to the fact that in making the well water-tight, the whole of her abaft the cabin bulkhead had been sealed up too; a veritable breeding-ground for stale air, with a promise of rot in the future. So I induced a through current of air in the lockers surrounding the well, and also under the floor, by putting a series of holes, not in the doors, but in the partitions; beginning at the cabin and ending at the after-locker door, in which I made three holes. This cured the trouble at once; the intake, indeed, at the after locker on a cold night, when the cabin is warmed by the stove, being enough to deflect the flame of a lighted match.

If you analyse it, there are only three absolute essentials in a cabin - a tight roof, a place to stretch out at full length, and some means of cooking food. Shelter, sleep, and sustenance; anything else you may manage to embroider on those three is so much to the good, but they are bedrock, and cannot be done without.

Rani had the first two, but only haphazard provision had been made for the third. Now I am not one of those who flout the call of appetite. A man half-fed is a man half-dead all the world over, and doubly so at sea. Food, hot and handy, is the thing that counts on a long drag; a well-fed crew makes a happy ship; and I count it evidence of better seamanship to be able to turn out a hot meal in spite of bad weather than to go empty because of it.

In accordance with these views, then pnd following a theory I have, that space should be allotted according to its relative importance, the galley had due prominence aboard Rani. One bunk had been successfully shortened to take the coal-stove, so I caused the same to be done to the other, obviously at the after-end, for handiness. Thus I got a platform of good area, conveniently raised, covered with linoleum, stuck down deck-fashion and divided from the bunk by a head-piece a foot high. I would not bulk-head it to the roof. Boxed-in galleys are always awkward, wasteful of space, and liable to collect dirt.

A swinging stove-stand is a necessity at sea. At the same time it is not wanted at anchor in smooth water. I therefore fitted a detachable one, fixed on the platform by a sash-screw. For such a fitting, a weighted board to stand the stove on, connected to two bearings of some sort level with the top of the stove, are about all that are needed in principle, whilst efficiency in action depends on the following:-

Allow for the "roll," but not for the "pitch." A boat's nose does not rise to a sea nearly so much as it seems to do. To gimbal both ways not only complicates construction but is unnecessary, and makes the galley too lively. Keep the centre of gravity high: i.e., arrange the counterpoise so that it just balances the heaviest cooking utensil in use. Set the bearings fore-and-aft, parallel with the keel-line, and not with the side of the boat.

For actual means of cooking, I used to rely, like most other cruisers in small boats, on a couple of "Primuses," until I came across a little wick-stove called the "Blue-flame Beatrice," which promptly displaced one "Primus." This stove burns with a "Bunsen" flame, does not smoke, lights at once, and can be left to look after itself when turned down low, which is not the case with the "Primus." For all purposes except a quick boil, I have found it admirable, and if stood in an oil-tight tray it is also cleanly.

The cabin-fittings had added, maybe, 30 lbs. deadweight of material, and although the boat was better trimmed, it had to be made up somewhere. I sought a sacrifice, and found it in the mainboom, a heavy spar of solid red fir. Out it came, and in went a bamboo, which made such a difference to the boat as I could not have believed, without trial, and which more than compensated for the extra weight below.

When structural alterations were complete there were still a host of minor things to be done. Each week-end discovered something to be chocked or bracketed into place, but not very long since, the little ship had occasion to put to sea with no other preparation than the hauling-down of two reefs in the mainsail. The passage lacked nothing in liveliness, but when she brought up, not a thing had fetched away below, all was as it had been before the start, and dry.

For the first time in a good many years, and in not a few boats, there was nothing waiting to be done. The tool-bag laid to rest, the indent-sheet was clean at last and on it I could write "Finis."

The other side of the boat abreast the mast was left open for access to the hatch and fore-peak. The forehatch was made tight by screwing it down on to felt-covered "draught-excluder" with a thumbscrew and a bar across the underside of the opening. It may be worth noting that I have found the felt-covered "excluder" the only kind with any lasting quality in it. The plain rubber patterns perish in a few weeks.

I record here, for the benefit of anyone similarly troubled, that no sooner had I taken the boat over than I become aware of a strong musty smell, which I eventually traced to the fact that in making the well water-tight, the whole of her abaft the cabin bulkhead had been sealed up too; a veritable breeding-ground for stale air, with a promise of rot in the future. So I induced a through current of air in the lockers surrounding the well, and also under the floor, by putting a series of holes, not in the doors, but in the partitions; beginning at the cabin and ending at the after-locker door, in which I made three holes. This cured the trouble at once; the intake, indeed, at the after locker on a cold night, when the cabin is warmed by the stove, being enough to deflect the flame of a lighted match.

If you analyse it, there are only three absolute essentials in a cabin - a tight roof, a place to stretch out at full length, and some means of cooking food. Shelter, sleep, and sustenance; anything else you may manage to embroider on those three is so much to the good, but they are bedrock, and cannot be done without.

Rani had the first two, but only haphazard provision had been made for the third. Now I am not one of those who flout the call of appetite. A man half-fed is a man half-dead all the world over, and doubly so at sea. Food, hot and handy, is the thing that counts on a long drag; a well-fed crew makes a happy ship; and I count it evidence of better seamanship to be able to turn out a hot meal in spite of bad weather than to go empty because of it.

In accordance with these views, then pnd following a theory I have, that space should be allotted according to its relative importance, the galley had due prominence aboard Rani. One bunk had been successfully shortened to take the coal-stove, so I caused the same to be done to the other, obviously at the after-end, for handiness. Thus I got a platform of good area, conveniently raised, covered with linoleum, stuck down deck-fashion and divided from the bunk by a head-piece a foot high. I would not bulk-head it to the roof. Boxed-in galleys are always awkward, wasteful of space, and liable to collect dirt.

A swinging stove-stand is a necessity at sea. At the same time it is not wanted at anchor in smooth water. I therefore fitted a detachable one, fixed on the platform by a sash-screw. For such a fitting, a weighted board to stand the stove on, connected to two bearings of some sort level with the top of the stove, are about all that are needed in principle, whilst efficiency in action depends on the following:-

Allow for the "roll," but not for the "pitch." A boat's nose does not rise to a sea nearly so much as it seems to do. To gimbal both ways not only complicates construction but is unnecessary, and makes the galley too lively. Keep the centre of gravity high: i.e., arrange the counterpoise so that it just balances the heaviest cooking utensil in use. Set the bearings fore-and-aft, parallel with the keel-line, and not with the side of the boat.

For actual means of cooking, I used to rely, like most other cruisers in small boats, on a couple of "Primuses," until I came across a little wick-stove called the "Blue-flame Beatrice," which promptly displaced one "Primus." This stove burns with a "Bunsen" flame, does not smoke, lights at once, and can be left to look after itself when turned down low, which is not the case with the "Primus." For all purposes except a quick boil, I have found it admirable, and if stood in an oil-tight tray it is also cleanly.

The cabin-fittings had added, maybe, 30 lbs. deadweight of material, and although the boat was better trimmed, it had to be made up somewhere. I sought a sacrifice, and found it in the mainboom, a heavy spar of solid red fir. Out it came, and in went a bamboo, which made such a difference to the boat as I could not have believed, without trial, and which more than compensated for the extra weight below.

When structural alterations were complete there were still a host of minor things to be done. Each week-end discovered something to be chocked or bracketed into place, but not very long since, the little ship had occasion to put to sea with no other preparation than the hauling-down of two reefs in the mainsail. The passage lacked nothing in liveliness, but when she brought up, not a thing had fetched away below, all was as it had been before the start, and dry.

For the first time in a good many years, and in not a few boats, there was nothing waiting to be done. The tool-bag laid to rest, the indent-sheet was clean at last and on it I could write "Finis."

The Yachting Monthly, November, 1911