Small Craft

Late 19th & Early 20th Century British Yachting

The Sailors: Amateur British & Irish Yachtsmen Before World War One

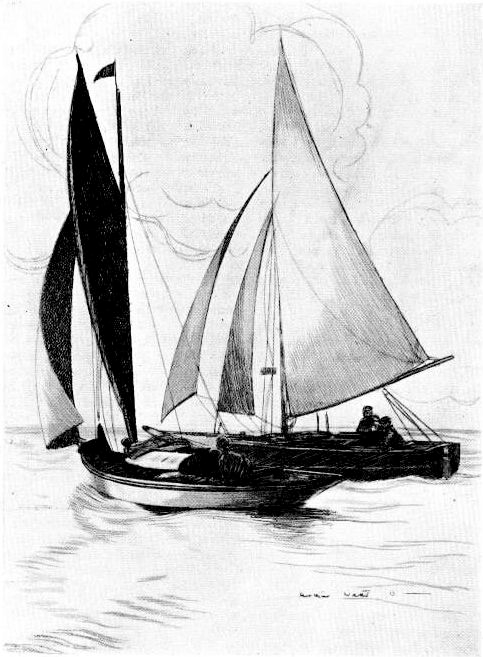

This is an account of a three-legged cruise from Burnham-on-Crouch to France, along the coast of France and Belguim to Holland, and back again. I call it a three-legged cruise because that seems the most adequate phrase by which to describe it. We had two boats between three men and sailed in company, so that one of us was always single-handed. First (alphabetically, anyway) comes Alterlie, a respectable Ithcen Ferry type of 4 tons. Second, Mave-Rhoe, a more modern boat of 3 tons. Alterlie is sturdy and solid, like a buxom country body. Mave-Rhoe, with more delicate lines, has a town-bred air

Alterlie has a length O.A. of 22ft., and being straight stemmed and transom-built her waterline is nearly the same. Her beam is 8ft., and as practically every inch of her is "boat," as the saying goes, she has a surprisingly comfortable cabin in spite of these modest dimensions. For canvas she carries a loose-footed, high-peaked mainsail with rather a heavy gaff, a fore-sail, and jib. Mave-Rhoe is, beside her, a comparatively fragile affair, has a length O.A. of 27ft., a waterline of 22, and a beam of 6ft. 6ins. Being a centreboard boat drawing 6ft. with, and 3ft. without her plate, she will point a little higher than the other, but for this advantage one pays dearly in the matter of cabin accommodation. She is intended primarily for single-handed sailing, is sloop-rigged, and fitted, not altogether to her owner's satisfaction, with reefing gear.

William had command of Alterlie, Oswald was his crew, while by force of circumstances Mave-Rhoe must needs voyage single-handed. William is skilled and wary, and has much cunning, but Oswald, before this cruise, was no true seafarer, and until we taught him better, had too much love for those land-locked waters, the Norfolk Broads. And that rather brings me to the purpose of this article, which is to show that with an ordinary degree of caution, a good glass and average summer weather, one may with perfect safety take a three-tonner to Holland and back from Burnham or any East coast port. The first time Mave-Rhoe made the passage we crossed straight from Harwich to Flushing, but I believe that to be a bad plan, and for this reason: In so small a boat one must have fair weather. And with fair weather it is five chances to one that the breeze, probably none to strong in the day, will fail altogether at night, and leave one rolling and wallowing about, heartily sick of the whole business.

However, to get back to this particular cruise. It is a curious fact that, however much time one may allow for buying and stowing away stores; however lengthy and complete may be one's list, there is at the last almost inevitably something that is forgotten. On this occasion it was Mave-Rhoe's red ensign. Now, everybody has his little vanity, and Mave-Rhoe's is to swagger into port with an ensign at her masthead. Abroad it does not seem to matter very much, and, with the exception of Dunkirk, where the Duoaniers have a very pretty taste on whisky, they don't seem to take any notice of one; but coming back it is a different thing, and I maintain that to come lurching into Ramsgate Harbour, bring up alongside a 50-tonner, run up your red ensign and light up your four-a-penny Dutch cigar while you wait for the representative of His Majesty's Customs to come aboard you, is a very neat bit of work. And after all, if when His Majesty's representatives do come alongside they wear a broad grin, that is because they are impertinent fellows, and do not know their place. You will understand, then, that a red ensign had to be found. Tucker Brown had none, Cranfield and Carter had just sold their last, King could not get one in less than a couple of days; and the shops were no better. Union Jacks, Royal Standards, Stars and Stripes, "fancy" flags--as many as you wished for, but nowhere a red ensign. And then, just as we had given up all hope, we ran one to earth in a draper's. A cheap thing, about the size of a pocket handkerchief, its price was "six-three," but there it was, the only one of its kind, and we had to make the best of it.

I shall not easily forget the glory of that start when we did finally get away from Burnham. A cool June morning with a steady following breeze, and a clear three weeks of cruising ahead. One could ask no more of Fate. The river's mouth behind us, we turned at the Ridge Buoy and cut across the Maplin Sands into the Swin; then edging round the Barrow held straight across the Knock-John (where there was none too much water,) and so came out into the deep water of the Duke of Edinburgh Channel. We were close-hauled with a fresh breeze and just enough sea to give one that sense of exhilaration that comes when sailing to windward, and standing out about two miles from the Foreland, lay over on the other tack for Ramsgate. The breeze lessened as we drew near the town, and by the time we had made the harbour and berthed in the western gulley it had died away altogether. It was pleasant to go aboard Alterlie after being alone all day, pleasant to talk over the events of the day after dinner. I suppose that no passage is so entirely devoid of incident that one has nothing to say about it, and so of this--the most uneventful trip imaginable--we talked as though we had not met for a week, and, dinner over, sat smoking on Alterlie's cabin-top watching the lights of the town reflected in the quiet water. Berthed near to us was an old smack, with whose skipper we presently struck up a desultory conversation. In one of its lulls I ventured to congratulate him on the astounding strength of his shrouds, which looked as though they were intended for a 100-tonner instead of his little half-decked craft.

"They were a cheap lot, them shrouds."

"Lor' love you, yes Sir, bless you," he said, "they were a cheap lot, them shrouds. I bought 'em for a shillin' off the Hotel Metropole at Brighton. They're bits of the cable what used to work the lift!" And he went on to give us the most minute details of the bargain until sleep overtook us all, and I returned to Mave-Rhoe for the night.

When we turned out the next morning a fresh breeze was blowing, a little too fresh for our timid wishes, and, what was much more disconcerting, the glass was dropping. We had intended to start at 3.30 a.m., but under the circumstances decided to wait until the afternoon, and in the meantime to send a wire to the Meteorological Office for a weather report. When, after breakfast, we walked to the end of the wall and had a look at the harbour mouth, we were inclined to think that we had done wisely; for the wind was coming straight into the harbour, as was also the tide. At the mouth there was a certain amount of popple; it looked little enough from above, but it was not improbable that a small boat trying to get out--blanketed, perhaps, by the wall before she could get enough way on her--would refuse to come about and drive back on to the harbour wall. As a matter of fact, we could have got warped out for half-a-crown, but that we found out too late. The wire dispatched to the Meteorological Office, we amused ourselves by watching the Ramsgate smacks coming out. It was a fine sight to see them tear across the harbour with a beam wind, luff smartly at the entrance, and come shooting out of the harbour with sails all shaking. The distances a heavy type of boat like this can shoot is to me amazing, and had we tried the same method I have no doubt whatever that it would have ended in ignominious failure. Our wire came at last, and with some anxiety we read its contents, which to our great joy promised fair weather with moderate breezes. This quite reassured us and any little sinking feeling that any of us, may have experienced in the pit of the stomach quite disappeared. So off we set, Mave-Rhoe first, Alterlie to follow shortly.

When we turned out the next morning a fresh breeze was blowing, a little too fresh for our timid wishes, and, what was much more disconcerting, the glass was dropping. We had intended to start at 3.30 a.m., but under the circumstances decided to wait until the afternoon, and in the meantime to send a wire to the Meteorological Office for a weather report. When, after breakfast, we walked to the end of the wall and had a look at the harbour mouth, we were inclined to think that we had done wisely; for the wind was coming straight into the harbour, as was also the tide. At the mouth there was a certain amount of popple; it looked little enough from above, but it was not improbable that a small boat trying to get out--blanketed, perhaps, by the wall before she could get enough way on her--would refuse to come about and drive back on to the harbour wall. As a matter of fact, we could have got warped out for half-a-crown, but that we found out too late. The wire dispatched to the Meteorological Office, we amused ourselves by watching the Ramsgate smacks coming out. It was a fine sight to see them tear across the harbour with a beam wind, luff smartly at the entrance, and come shooting out of the harbour with sails all shaking. The distances a heavy type of boat like this can shoot is to me amazing, and had we tried the same method I have no doubt whatever that it would have ended in ignominious failure. Our wire came at last, and with some anxiety we read its contents, which to our great joy promised fair weather with moderate breezes. This quite reassured us and any little sinking feeling that any of us, may have experienced in the pit of the stomach quite disappeared. So off we set, Mave-Rhoe first, Alterlie to follow shortly.

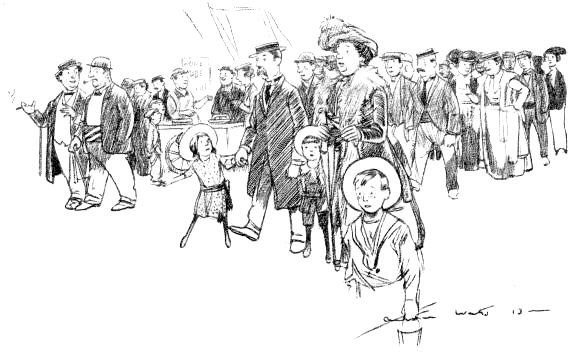

"Going foreign."

Safely out of the harbour and through the Cudd Channel, I hove to and waited, fairly revelling in the sense of space and freedom that deep water gives after the confinement of a harbour. Ramsgate but an hour or so ago had been a crowded sweltering place in whose streets one was elbowed and shoved by throngs of perspiring trippers. The thousand and one noises of a seaside town assaulted one's ears; one's eyes were wearied by the clamorous posters that invited one to sixpenny teas. But seen in the afternoon sunshine, the coast had all that unreality and charm that the sight of it from seaward always brings. Ramsgate was a neat little toy town; the swarming trippers on the beach little black ants; and on either hand stretched the fertile country, dotted with tine woods and villages.

It is my experience—I wonder if it is other people's, too—that out of a season's sailing, out of all one's experience of sailing one might say, just one or two incidents as this, one or two vivid pictures, stand out pre-eminently. It may be the merest trifle; perhaps the memory of a pipe of tobacco smoked after a long and anxious passage, or the slipping away from one's moorings on a still October morning--it is of such trifles that one loves to thnk again and again in the gas-lit winter evenings.

It is my experience—I wonder if it is other people's, too—that out of a season's sailing, out of all one's experience of sailing one might say, just one or two incidents as this, one or two vivid pictures, stand out pre-eminently. It may be the merest trifle; perhaps the memory of a pipe of tobacco smoked after a long and anxious passage, or the slipping away from one's moorings on a still October morning--it is of such trifles that one loves to thnk again and again in the gas-lit winter evenings.

"Throngs of Perspiring Trippers."

Presently a little white patch that I recognised as the Alterlie came dipping out from behind the harbour wall, and as she came up to me I let my jib draw and together we headed for the North Goodwin. That passed we had the wind on our beam, and I could lash my helm and make tea. Hour after hour we bowled along, the white cliffs of Sandgatte plainly visible. As the sun came near to its setting we could see the low coast that lies between Gravelines and Calais--could see Gravelines itself, and then with the deepening twiglight lost it again. The breeze fell light now, but we had the tide with us, and there was no need to hurry. I saw Alterlie's lights gleam out, and presently in the dinghy came Oswald to bear me company. As we held on our way up the coast we could hear sounds from the shore--a train--a dog barking--a French dog--as the excited Oswald said. We should have picked up the Snouw lightship, but owing to its having been temporarily replaced by a buoy we missed it, and were fairly in that brilliantly lighted fairway that leads to Dunkirk before we knew exactly where we were. It was nearly midnight before we were off the harbour, and very mysterious it looked with its innumerable twinkling lights, the dark shadow of the piles below, and the lapping water.

With my short gaff I was completely blanketed by the jetty, while Alterlie, more fortunate, came by like a liner, and for once, as I sculled my laborious way up the harbour, I envied her her high-peaked mainsail.

Arrived at last at the public quay, William laid his kedge out, carried a bow and stern warp to the quay, and hauled out broadside on to the kedge while I lay alongside him on the inner side. Then, my gear stowed, I went aboard Alterlie, to whose cabin the Douaniers had already penetrated.

Like cheery well-fed robins they sat there, drinking William's whisky, and in the inconsiderable pauses between drinks their honest cheeks bulged with his biscuits. But they were welcome enough. We were much too content with ourselves and all the world to grudge them a little refreshment, and while they made out our passports we drank to their jolly good selves and La Belle France. They are most magnificent documents, these Dunkirk passports, and amongst other things the President of the French Replublic assures you of his distinguished sentiments. And so he ought when you have to pay two francs for them!

Our guests were in no hurry. I daresay they found Alterlie's cabin a vast improvement on the cold darkness outside, and by the time we finally did get rid of them the dawn was breaking. In the grey half-light William and Oswald looked like a couple of haggard tramps, and I daresay I looked no better, but we were in no mood for sleep yet, and sat about watching Dunkirk slowly reveal itself in detail. The wharves were deserted; no sound came from the sleeping town except the sonorous chimes that rang out now and again from the Town Hall, and the only living creature within sight was an elfish old man on the quayside above our heads. He kept up an interminable sibilant whispering, for whose benefit we could not see, and as we sat about on Alterlie's cabin-top (the only place to sit on Alterlie!) we pondered lazily as to the subject of his discourse, why he should choose this unearthly hour for it, and most of all, why his listener should continue to be his listener. However, he departed at last and we turned in in broad daylight just as the town began to stir.

The next day we spent in idleness, for Dunkirk is too fine a town to slip in and out of again without a few hours on shore. And also, when weeks--months--ago we had planned this cruise, we had determined that we would sit in a certain cafe that overlooks the Place Jean Bart and drink the wine of the country. It was tempting Fate, I suppose, and we deserved to be shipwrecked for our presumption, but for once she was kind and gave us a sunny day for our junketing into the bargain. In the afternoon, only three parts awake, we exchanged the cafe for the little public garden that lies in the centre of the town. They laying out of these little public gardens is, I think, one of those things that they do better in France. They manage to create an atmosphere about them, a homeliness, that is sadly lacking in our corresponding attempts. And this is one of the very best. It is a tiny place, green and peaceful, and in its centre is a little circular basin in which a fountain plays. Round the basin is a gravel path, and round that again are seats on which in the drowsy summer evenings the townsfolk take their ease. The children play with the water, the little dogs bark, fat placid "bonnes" gossip with the imposing old gentleman in uniform who is responsible for law and order, and altogether there is an air of quiet content over the whole place.

For the rest Dunkirk is just a fine hearty seaport with excellently equipped docks. It has its "plage" which in the summer is crowded with trippers, but that is away from the town, and one might stay for a week in the place and not be aware of its existence.

Part Two

With my short gaff I was completely blanketed by the jetty, while Alterlie, more fortunate, came by like a liner, and for once, as I sculled my laborious way up the harbour, I envied her her high-peaked mainsail.

Arrived at last at the public quay, William laid his kedge out, carried a bow and stern warp to the quay, and hauled out broadside on to the kedge while I lay alongside him on the inner side. Then, my gear stowed, I went aboard Alterlie, to whose cabin the Douaniers had already penetrated.

Like cheery well-fed robins they sat there, drinking William's whisky, and in the inconsiderable pauses between drinks their honest cheeks bulged with his biscuits. But they were welcome enough. We were much too content with ourselves and all the world to grudge them a little refreshment, and while they made out our passports we drank to their jolly good selves and La Belle France. They are most magnificent documents, these Dunkirk passports, and amongst other things the President of the French Replublic assures you of his distinguished sentiments. And so he ought when you have to pay two francs for them!

Our guests were in no hurry. I daresay they found Alterlie's cabin a vast improvement on the cold darkness outside, and by the time we finally did get rid of them the dawn was breaking. In the grey half-light William and Oswald looked like a couple of haggard tramps, and I daresay I looked no better, but we were in no mood for sleep yet, and sat about watching Dunkirk slowly reveal itself in detail. The wharves were deserted; no sound came from the sleeping town except the sonorous chimes that rang out now and again from the Town Hall, and the only living creature within sight was an elfish old man on the quayside above our heads. He kept up an interminable sibilant whispering, for whose benefit we could not see, and as we sat about on Alterlie's cabin-top (the only place to sit on Alterlie!) we pondered lazily as to the subject of his discourse, why he should choose this unearthly hour for it, and most of all, why his listener should continue to be his listener. However, he departed at last and we turned in in broad daylight just as the town began to stir.

The next day we spent in idleness, for Dunkirk is too fine a town to slip in and out of again without a few hours on shore. And also, when weeks--months--ago we had planned this cruise, we had determined that we would sit in a certain cafe that overlooks the Place Jean Bart and drink the wine of the country. It was tempting Fate, I suppose, and we deserved to be shipwrecked for our presumption, but for once she was kind and gave us a sunny day for our junketing into the bargain. In the afternoon, only three parts awake, we exchanged the cafe for the little public garden that lies in the centre of the town. They laying out of these little public gardens is, I think, one of those things that they do better in France. They manage to create an atmosphere about them, a homeliness, that is sadly lacking in our corresponding attempts. And this is one of the very best. It is a tiny place, green and peaceful, and in its centre is a little circular basin in which a fountain plays. Round the basin is a gravel path, and round that again are seats on which in the drowsy summer evenings the townsfolk take their ease. The children play with the water, the little dogs bark, fat placid "bonnes" gossip with the imposing old gentleman in uniform who is responsible for law and order, and altogether there is an air of quiet content over the whole place.

For the rest Dunkirk is just a fine hearty seaport with excellently equipped docks. It has its "plage" which in the summer is crowded with trippers, but that is away from the town, and one might stay for a week in the place and not be aware of its existence.

Part Two