Small Craft

Late 19th & Early 20th Century British Yachting

The Sailors: Amateur British & Irish Yachtsmen Before World War One

The following day we got under way about twelve for Zeebrugge. Once out of the harbour the wind was dead fair, and we made a fine rate of speed. Through the Zuidcoote Pass, the narrow channel between Braeck and the Traepegeer Sands we had to keep along the coast to Zeebrugge. There is little enough in the way of scenery, it must be granted--sand dunes and clusters of box-like buildings all the way--but with a sunny day and a following breeze that was no great matter. Past La Panne--the last town on the French coast--and we were off Belgium, and shortly after Nieuport became visible. Mave-Rhoe is not a stranger to it, and a few hints on its harbour may not be out of place.

There is water in the entrance at any state of tide, but do not bring up in the first straight channel. You may see fishing boats lying there, but these dry out. Continue up the harbour, bear to the starboard and make fast at the quay immediately before you come to the lock gates. Or, if you fear for your paint, as the fishing boats, none too tenderly handled, also lie here, you may lock into the basin, which is a safe and quiet berth, albeit a little dreary. Should a withered man in blue serge, having the air of an official, try to board your boat, brain him or throw him into the water, for he is the devil in disguise. After Nieuport we passed Ostend, of which I shall have something to say on our homeward journey, and later on Blankenberge, from which one can plainly see the great breakwater of Zeebrugge. Blankenberge is a good enough harbour, but with a narrow entrance, up which only a small and handy boat can tack. This opens out into a basin, where one can lie at one's anchor.

There is water in the entrance at any state of tide, but do not bring up in the first straight channel. You may see fishing boats lying there, but these dry out. Continue up the harbour, bear to the starboard and make fast at the quay immediately before you come to the lock gates. Or, if you fear for your paint, as the fishing boats, none too tenderly handled, also lie here, you may lock into the basin, which is a safe and quiet berth, albeit a little dreary. Should a withered man in blue serge, having the air of an official, try to board your boat, brain him or throw him into the water, for he is the devil in disguise. After Nieuport we passed Ostend, of which I shall have something to say on our homeward journey, and later on Blankenberge, from which one can plainly see the great breakwater of Zeebrugge. Blankenberge is a good enough harbour, but with a narrow entrance, up which only a small and handy boat can tack. This opens out into a basin, where one can lie at one's anchor.

Off Blankenberg.

On this occasion, however, we were bound for Zeebrugge, which I had heard made a better anchorage. The tide had turned now, and, although the breeze held well, it seemed a long time before we crept round the end of the great breakwater at last, and made for the entrance to the Bruges canal. The change from the rough and tumble outside was very pleasant, for this great sea wall, more than a mile in length, encloses a vast area of water, and with a following wind such as we had this was protected by it and as still as a mill pond. Finally we brought up near the lock gate, mooring bow and stern to the dolphins. It may be worth while to point out that should one moor on the starboard hand, an electric wire (by a singularly bad piece of construction) is very much in the way, so that if all the port dophins are occupied it is better to lie to one's anchor inside of the starboard ones, with a stern rope to the quay above. It is an excellent anchorage, absolutely quiet, and from it one may watch the great Rhine skiffs being towed through the lock that is the entrance to the Bruges Canal. It was again a straight run up the coast the next day--past the same sand dunes anad clusters of box-like buildings. The mouth of the Scheldt gained, we pottered into the little Dutch harbour of Breskens, which is on the starboard hand side going in. It is a pleasant little place, with plenty of water for small boats, and were one going on up the Scheldt to Antwerp instead of--as we did--locking into the Flushing-Middleburg Canal, it would make a convenient harbour to lie in for the night. However, as we wished to reach Middleburg that evening, we did not bring up, but headed for Flushing. We were soon through the lock, but once under the lee of the tree-shaded banks of the canal we could get no wind, and scarcely moved. Finally we took it in turns to tow from the bank, Mave Rhoe being made fast astern of Alterlie. Thus we alternated between the most exquisite leisure and heart-breaking toil. To sit steering in the well, contendedly watching the straining figure on the bank was one thing, to be that figure, panting and streaming with perspiration, was another. William, who is unemotional and philosophic by nature, took the business calmly enough, but for my part I must confess the sound of the breeze rustling the tree tops exasperated me almost beyond endurance.

Middleburg's tall white spire showed up above the trees at last, and the chimes welcomed us with Rubenstein's Melody in F. Had Rubenstein heard it I feel assured that he would have drowned himself on the spot, but for all its jangling incoherence there was a certain mellow charm about the sound that suited this still evening very well. It was dark by the time we neared the swing bridge that spans the canal just above the quays, and I got aboard Mave Rhoe again to scull her through. We neither of us knew the correct method of signalling that we wanted it to open--and the most terrific blasts on our fog horns availing nothing, Oswald approached the bank in Alterlie's dinghy. There he harangued three small boys, one of whom had a little English, and who told him that one must run a light up to the masthead. This light at the masthead is, by the way, apparently used instead of side-lights at night in Dutch waters. We were stopped later in the cruise by a Police Boat, and told that we must have them up, and this in spite of the fact that Alterlie's side-lights were burning brightly, and that Mave Rhoe's tricolour lamp would have been, had not her owner just fallen over it! It seems a poor substitute for side-lights, and one rather wonders at the Dutch, who are such fine watermen, having such a clumsy arrangement. However, up went our masthead lights, and although the bridge did not exactly fly back with a thud at the sight, it did eventually open, and we passed through. Ever since Oswald's small boys supplied him with the information about the masthead light they had been bursting with a desire to take us under their charge altogether, and to pilot us to a berth. From the bank they made seductive noises, "Pst....hst....hst....pst----." They were indefatigable. But we would have none of them. We hadn't come unaided all the way from England to be piloted to the bank of a perfectly quiet canal by three small boys, and, maintaining a stony silence, brought up at the public quay between two big canal boats. Needless to say, our counsellors were waiting for us, but I think the close proximity of the three mad foreigners intimidated them, for they presently slunk off into the darkness without so much as a syllable.

Middleburg's tall white spire showed up above the trees at last, and the chimes welcomed us with Rubenstein's Melody in F. Had Rubenstein heard it I feel assured that he would have drowned himself on the spot, but for all its jangling incoherence there was a certain mellow charm about the sound that suited this still evening very well. It was dark by the time we neared the swing bridge that spans the canal just above the quays, and I got aboard Mave Rhoe again to scull her through. We neither of us knew the correct method of signalling that we wanted it to open--and the most terrific blasts on our fog horns availing nothing, Oswald approached the bank in Alterlie's dinghy. There he harangued three small boys, one of whom had a little English, and who told him that one must run a light up to the masthead. This light at the masthead is, by the way, apparently used instead of side-lights at night in Dutch waters. We were stopped later in the cruise by a Police Boat, and told that we must have them up, and this in spite of the fact that Alterlie's side-lights were burning brightly, and that Mave Rhoe's tricolour lamp would have been, had not her owner just fallen over it! It seems a poor substitute for side-lights, and one rather wonders at the Dutch, who are such fine watermen, having such a clumsy arrangement. However, up went our masthead lights, and although the bridge did not exactly fly back with a thud at the sight, it did eventually open, and we passed through. Ever since Oswald's small boys supplied him with the information about the masthead light they had been bursting with a desire to take us under their charge altogether, and to pilot us to a berth. From the bank they made seductive noises, "Pst....hst....hst....pst----." They were indefatigable. But we would have none of them. We hadn't come unaided all the way from England to be piloted to the bank of a perfectly quiet canal by three small boys, and, maintaining a stony silence, brought up at the public quay between two big canal boats. Needless to say, our counsellors were waiting for us, but I think the close proximity of the three mad foreigners intimidated them, for they presently slunk off into the darkness without so much as a syllable.

A Memory of the Middleberg Canal.

Middleburg is an ideal berth for those who like that kind of thing. One has trees overhead and quiet canal water underneath, and if half the town watches you go to bed, it is but the price that has to be paid for such security. The quaint place must seem a singularly charming town, even to the casual tourist, weighed down as he is by hotel and transport worries. But whe you walk straight out of the cabin of your own little ship on to the quay and stroll about in the moonlight, as we did, unhurried and at home, its streets seem almost unreal in their romantic beauty. But that I take to be a charm peculiar to approaching a place by water. Over the most prosaic town there hangs a mist of romance, and when, as in this case, your objective is of itself beautiful, seen in this light, it becomes a veritable enchanted city. The next morning was devoted to sight-seeing, and in the afternoon we pottered on to Veere.

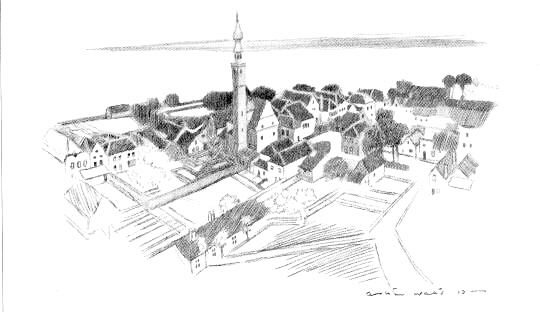

Veere from the Church Tower.

Veere is to my mind the most beautiful town imaginable. While we were at Middleburg, if William or Oswald paused to admire anything in particular, I would say jealously, "Ah, yes, that's all right in its way, but wait till you see Veere!" This, of course, was a mistake; as well introduce two of one's intimate friends to one another and expect the introduction to be a success. On looking back I have a horrible suspicion that with my reiterated phrases I became a little bit of a bore, and that their stolid acceptance of Veere as just a picturesque town among others was a deserved Nemesis. It is difficult to explain the attraction that the place has for one, and did I try, and were you one day to visit it, you might say, "Yes, yes, it's all right; but I don't know that it's more beautiful than Tholen or Zerixee," or any other town you might have just left. So I will say nothing more than its most casual admirer might say. It is just a little rather melancholy town set among trees, looking out over the sea. It has a vast ruined church, a windmill and a town-hall that might have been a king's palace in a Hans Andersen's fairy tale. There is only one street (if you except the quay site), and in that the grass grows without let or hindrance. Once it was a great town, and kings and queens visited it. Now it is broken, and of no account. In the town-hall an intelligent custodian will show you pathetic records of its greatness, but while that vast church tower stands there is no need of other records. I'm afraid that even this last sad beauty is waning. A shop, little as yet, proclaims that "Antiquities" are for sale; one cannot walk a hundred yards without falling over an artist, and the sons and daughters of America swarm all over the place.

We sailed to Zerixee the next day, taking the last of the ebb out of the Veergat, rounding the Onrust Sand, and catching the young flood up the Roompot. This Onrust Sand, by the way, is a dangerous one, gravel for the most part (three years ago Mave Rhoe found that out to her cost), and it is suicidal to attempt to sneak inside any of the buoys that mark it. A mile long channel leads to Zerixee--straight as a spear--and with a head wind in anything over four tons it is a weary business. But in any circumstances the town repays the trouble. It is a large place, nearly as large as Middleburg, but without its bustling life. There is a church tower (the church is no more), which is, I should imagine, as fine a specimen of fifteenth century work as may be found in Holland. A few paces away is the modern church, a building in the classical style. At a little distance it has the appearance of being solidly build of stone, but is really built entirely of wood--even the pillars that support its portico are not stone. To really appreciate Zerixee--and, indeed, all these old Netherland towns--one should read, before visiting them, Motley's "Dutch Republic." I think that no book could inpire one with so much respect for the Dutch people. Through it one can gain some little insight into their character, understand a little of the tenacity of purpose that underlies their apparent stolidity. The Spaniards left their mark at Zerixee, by the way, in the shape of a singularly beautiful building, which, I must confess, goes but ill with the terrible character that Motley gives them. It is difficult to believe that it could ever have been planned by such ferocious creatures as he shows us. The streets of the town are cobbled and tree-shaded, and almost every other house is beautiful; if not in its entirety, then in some minor detail.

For some reason which I have forgotten we wished to lie at Veere that night, and in the afternoon got under way. Oswald, for a change, sailed on Mave Rhoe, and before we got away ourselves we cast off Alterlie's warps and saw her disappear round the bend that hides the straight channel alongside the quay from the far longer one that leads to the entrance. We got away soon after, and when we had turned the corner beheld a tragedy. For there was Alterlie, nose up on the bank, and there was William pushing, pulling, leaping, trying with all his might and main to get her boom over to blow her off. The tide was ebbing, and it was a matter of minutes, but just as we came up to him (feeling a little anxious, for the bank was steep) he got off. I knew what had happened--I would have bet upon it. William, like most of us, is for all his cautiousness and guile human. And he has a weakness. He will heave to in a ditch and go below to cook bacon. But I think it is for the most part loyalty to Alterlie. He believes that once hove to she remains motionless, and has the courage of his convictions, so that this very excusable weakness of his is but a proof of his devotion to his boat.

Out in open water again we found the broad expanse all foam-capped and turbulent. From the distance, where the sky had become inky black, came the rumbling of thunder, and against the indigo masses of storm cloud the crawling lines of foam seemed dazzlingly white. Here and there a buoy made a spot of colour, and far away, over Bergen-op-Zoom, a sudden shaft of sunlight turned the low land to vivid green. But it was nothing worse than a summer storm, and soon passed over, leaving sunshine and blue sky behind.

It was a curious thing that, as we drew near Veere, I commented to Oswald on the lack of incident that up till now had characterised our cruise. It had been as smooth and triumphant as a Lord Mayor's show, with none of those difficulties and indignities that often beset the small boat sailor. Fate overheard me, I think. Veere has a harbour, the usual little mousetrap of a place, and we decided that instead of locking into the canal and out again in the morning we would lie in this harbour for the night. I, who should have known better (having been to Veere before) thought that there was enough water; at all events, could not remember seeing it dry. And so we sailed in like sheep to the slaughter. We had a beam wind, and William, reckless for once, sailed in with all his canvas set. Mave Rhoe followed, and, alas! hugging the pierhead too closely lest she should get swept on to the other, found herself aground. While we pushed and pulled I had a glimpse of Alterlie, safe in, but aground, too. A few moments, and we were off again. I saw Alterlie charge up the narrow ditch and come hard up with tremendous way on, and I held my breathe during the moments before she should smash her bowsprit on the quay. But she never reached the quay; she had struck again; and I saw William with that calmness which betokens utter despair letting his gear down. We realised now, of course, what was the matter. We were in a channel so narrow that we could not hope to turn, and could not hope to get out again. I have but a confused remembrance of stolid faces looking down at us from the quay, placidly enjoying the spectacle, and finally Alterlie and Mave Rhoe were lying side by side in about four feet of water and the tide only at half ebb. The one figure that stands out clearly is the agonised owner of the great botter alongside which we brought up, in a perfect fever lest Mave Rhoe should damage his craft. It was an ignominious affair, and we all, I think, felt sick and sorry. I regret to say that some English girls (art students, I suspect) were amongst the crowd on the quay, and as I scrambled up the botter's mast to make a line fast that should keep Mave Rhoe from tumbling over when the water fell, they laughed unrestrainedly. It has since occurred to me that they laughed because my trousers had no seat, but at the time there was no such balm to soothe me, and as I slid down on deck again I could have danced for rage. To think that we, we who had come from over the sea, should make sport not only for Dutch boors in a ditch, but for our own compatriots, was more than I could bear, and I believe it was only Williams' outwardly calm and unruffled demeanour that kept me from a shameful outburst. However, the irritation soon died away, and, as a consolation, we dined ashore, rather indifferently. But Veere wil never be quite the same again, and I don't think I shall ever quite forgive those English girls!

We sailed to Zerixee the next day, taking the last of the ebb out of the Veergat, rounding the Onrust Sand, and catching the young flood up the Roompot. This Onrust Sand, by the way, is a dangerous one, gravel for the most part (three years ago Mave Rhoe found that out to her cost), and it is suicidal to attempt to sneak inside any of the buoys that mark it. A mile long channel leads to Zerixee--straight as a spear--and with a head wind in anything over four tons it is a weary business. But in any circumstances the town repays the trouble. It is a large place, nearly as large as Middleburg, but without its bustling life. There is a church tower (the church is no more), which is, I should imagine, as fine a specimen of fifteenth century work as may be found in Holland. A few paces away is the modern church, a building in the classical style. At a little distance it has the appearance of being solidly build of stone, but is really built entirely of wood--even the pillars that support its portico are not stone. To really appreciate Zerixee--and, indeed, all these old Netherland towns--one should read, before visiting them, Motley's "Dutch Republic." I think that no book could inpire one with so much respect for the Dutch people. Through it one can gain some little insight into their character, understand a little of the tenacity of purpose that underlies their apparent stolidity. The Spaniards left their mark at Zerixee, by the way, in the shape of a singularly beautiful building, which, I must confess, goes but ill with the terrible character that Motley gives them. It is difficult to believe that it could ever have been planned by such ferocious creatures as he shows us. The streets of the town are cobbled and tree-shaded, and almost every other house is beautiful; if not in its entirety, then in some minor detail.

For some reason which I have forgotten we wished to lie at Veere that night, and in the afternoon got under way. Oswald, for a change, sailed on Mave Rhoe, and before we got away ourselves we cast off Alterlie's warps and saw her disappear round the bend that hides the straight channel alongside the quay from the far longer one that leads to the entrance. We got away soon after, and when we had turned the corner beheld a tragedy. For there was Alterlie, nose up on the bank, and there was William pushing, pulling, leaping, trying with all his might and main to get her boom over to blow her off. The tide was ebbing, and it was a matter of minutes, but just as we came up to him (feeling a little anxious, for the bank was steep) he got off. I knew what had happened--I would have bet upon it. William, like most of us, is for all his cautiousness and guile human. And he has a weakness. He will heave to in a ditch and go below to cook bacon. But I think it is for the most part loyalty to Alterlie. He believes that once hove to she remains motionless, and has the courage of his convictions, so that this very excusable weakness of his is but a proof of his devotion to his boat.

Out in open water again we found the broad expanse all foam-capped and turbulent. From the distance, where the sky had become inky black, came the rumbling of thunder, and against the indigo masses of storm cloud the crawling lines of foam seemed dazzlingly white. Here and there a buoy made a spot of colour, and far away, over Bergen-op-Zoom, a sudden shaft of sunlight turned the low land to vivid green. But it was nothing worse than a summer storm, and soon passed over, leaving sunshine and blue sky behind.

It was a curious thing that, as we drew near Veere, I commented to Oswald on the lack of incident that up till now had characterised our cruise. It had been as smooth and triumphant as a Lord Mayor's show, with none of those difficulties and indignities that often beset the small boat sailor. Fate overheard me, I think. Veere has a harbour, the usual little mousetrap of a place, and we decided that instead of locking into the canal and out again in the morning we would lie in this harbour for the night. I, who should have known better (having been to Veere before) thought that there was enough water; at all events, could not remember seeing it dry. And so we sailed in like sheep to the slaughter. We had a beam wind, and William, reckless for once, sailed in with all his canvas set. Mave Rhoe followed, and, alas! hugging the pierhead too closely lest she should get swept on to the other, found herself aground. While we pushed and pulled I had a glimpse of Alterlie, safe in, but aground, too. A few moments, and we were off again. I saw Alterlie charge up the narrow ditch and come hard up with tremendous way on, and I held my breathe during the moments before she should smash her bowsprit on the quay. But she never reached the quay; she had struck again; and I saw William with that calmness which betokens utter despair letting his gear down. We realised now, of course, what was the matter. We were in a channel so narrow that we could not hope to turn, and could not hope to get out again. I have but a confused remembrance of stolid faces looking down at us from the quay, placidly enjoying the spectacle, and finally Alterlie and Mave Rhoe were lying side by side in about four feet of water and the tide only at half ebb. The one figure that stands out clearly is the agonised owner of the great botter alongside which we brought up, in a perfect fever lest Mave Rhoe should damage his craft. It was an ignominious affair, and we all, I think, felt sick and sorry. I regret to say that some English girls (art students, I suspect) were amongst the crowd on the quay, and as I scrambled up the botter's mast to make a line fast that should keep Mave Rhoe from tumbling over when the water fell, they laughed unrestrainedly. It has since occurred to me that they laughed because my trousers had no seat, but at the time there was no such balm to soothe me, and as I slid down on deck again I could have danced for rage. To think that we, we who had come from over the sea, should make sport not only for Dutch boors in a ditch, but for our own compatriots, was more than I could bear, and I believe it was only Williams' outwardly calm and unruffled demeanour that kept me from a shameful outburst. However, the irritation soon died away, and, as a consolation, we dined ashore, rather indifferently. But Veere wil never be quite the same again, and I don't think I shall ever quite forgive those English girls!

Driving a bargain, Walcherin Island.

We walked about the town the next morning, and climbed the church tower, from whence you may see a fine fertile country, intersected everywhere by water. In the afternoon we sailed to Kortgene, where Mave Rhoe, trying to nose her way up a creek, ran aground and had to be ignominiously hauled off the way she had come. We then anchored off Kortgene for the night. It is an unassuming town, but evidently a properous one, for they are making a little harbour. It is a most amazing thing that every village on the water's edge in Holland seems to have its harbour, and each little harbour is a model of neatness. There is none of that picturesque decay about the timber work that one associates with small English harbours. Every pile seems to have been freshly painted, and one can but envy a people who, having no army or navy worth the name to keep up, can afford to spend their money upon civil objects.

From Kortgene we sailed to Tholen, the capital, and I should say about the only town on the island of that name. We passed a fine English yacht as we beat up the Zuid Vliet, a big white ketch of some fifty tons. She had the wind dead fair and not a stitch of canvas set, but came "teuf-teufing" along with her auxiliary. We waved to them, but they made no response; perhaps it was below their dignity to wave to shabby little three-tonners, but I like to think it was beause they were ashamed, in this fine easterly weather, to be relying on their engine instead of bowling along under full sail. Such a day that was, as bright as a jewel, with a steady breeze, and a smother of spray. We raced a botter that was making for Tholen, too. But Mave Rhoe was foul, although a little faster than Alterlie, and, try as I might, I could not hold her.

One comes out from the narrow Veere channel into the broad stretch of the Englische Vaerwater. Good sailing water, seen at high tide, but in reality a perfect maze of sands. On the left hand one sees the opening to the Hansweert canal, by which one may pass into the Scheldt. It is crowded with traffic, and an awkward place for little boats. Threading our way through the various channels, we made for the left bank, after which it was plain sailing till we reached the mouth of the river, or creek, rather, on which Tholen lies. Ahead of us, some six miles away, we could see the factory chimneys of Bergen-op-Zoom, and a great stretch of sand banks only covered at high water. Before the Hansweert Canal was built, a boat of shallow draught could find her way into the Scheldt through these sands, but now the creek is blocked by the railway. It was among these, too, that a wonderful strategic coup was successsfully carried out by the Spaniards--and of this as of so much else that is inpiriting in the history of Holland one may learn in Motley.

From Kortgene we sailed to Tholen, the capital, and I should say about the only town on the island of that name. We passed a fine English yacht as we beat up the Zuid Vliet, a big white ketch of some fifty tons. She had the wind dead fair and not a stitch of canvas set, but came "teuf-teufing" along with her auxiliary. We waved to them, but they made no response; perhaps it was below their dignity to wave to shabby little three-tonners, but I like to think it was beause they were ashamed, in this fine easterly weather, to be relying on their engine instead of bowling along under full sail. Such a day that was, as bright as a jewel, with a steady breeze, and a smother of spray. We raced a botter that was making for Tholen, too. But Mave Rhoe was foul, although a little faster than Alterlie, and, try as I might, I could not hold her.

One comes out from the narrow Veere channel into the broad stretch of the Englische Vaerwater. Good sailing water, seen at high tide, but in reality a perfect maze of sands. On the left hand one sees the opening to the Hansweert canal, by which one may pass into the Scheldt. It is crowded with traffic, and an awkward place for little boats. Threading our way through the various channels, we made for the left bank, after which it was plain sailing till we reached the mouth of the river, or creek, rather, on which Tholen lies. Ahead of us, some six miles away, we could see the factory chimneys of Bergen-op-Zoom, and a great stretch of sand banks only covered at high water. Before the Hansweert Canal was built, a boat of shallow draught could find her way into the Scheldt through these sands, but now the creek is blocked by the railway. It was among these, too, that a wonderful strategic coup was successsfully carried out by the Spaniards--and of this as of so much else that is inpiriting in the history of Holland one may learn in Motley.