Small Craft

Late 19th & Early 20th Century British Yachting

The Sailors: Amateur British & Irish Yachtsmen Before World War One

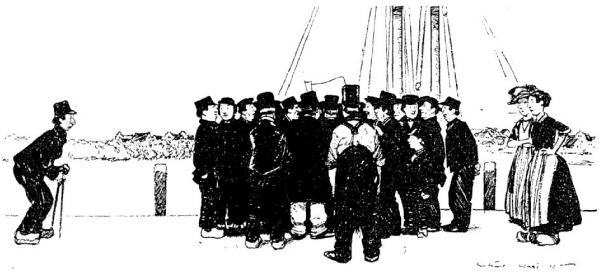

At length, after a splendid beat to windward, we arrived off the entrance to Tholen Creek. It is a difficult entrance, narrow, twisting, and although there are withies to mark the channel, its windings are so devious that they are of little use. However, by incessant use of the boat hook, we got in safely, Mave-Rhoe going aground once, but only momentarily, and we brought up off Tholen without further mishap. This, like Kortegene, is a prosperous little town with a beautiful old church. It has its harbor, too, which dries right out; but as the creek at this point is little wider than the Thames at Richmond, there is no need to enter it. Evidently, English yachts were a novelty, for had we been a party of red Indians in full war paint with birch bark canoes, we could not have caused greater excitement. William, unemotional and methodical as usual, must needs choose this fine summer day to decorate his stern with a band of vivid arsenic green, and it was not till the shadows were lengthening that we got ashore. Never shall I forget the sensation we caused (later on I discovered that it was largely because we wore no hats!) One could not say that we were mobbed; that would imply hostility. We were simply squeezed. We had taken a chart ashore because tomorrow's passage involved crossing the watershed of the narrow creek which separates Tholen from the mainland. Selecting, therefore a group of intelligent-looking fishermen, we unrolled our chart and began to explain in pantomime. Instantly all Tholen had closed round us, and we found ourselves at the center of an open-mouthed, round-eyed, laughing crowd. Even William was overcome, and forgot what few scraps of Dutch he had learnt. But our fishermen understood all right, and not only they, but the entire crowd, and in the most deafening babel of voices I have ever heard sought to give us information. There was plenty of water in the creek at high tide, and we could safely make our passage. Finally, perspiring and grinning, we fought our way out of the throng and made off up the town to buy provisions. But if we though that a show like ourselves, the rare, spicy and delectable spectacle of three mad and hatless foreigners, in incredible clothes, were to pass unobserved, we were soon to find out our mistake.

"All Tholen crowded round us."

The children simply loved us. At the first shop at which we called there were about half a dozen noses flattened against the window. At the second a dozen, ands after that we seemed to head a triumphal procession. Shopping is a trying enough business at any time, but when you find yourself utterly unable to ask for what you want and your efforts to explain watched by a perfect sea of faces, it becomes impossible, and when we eventually found a good man who spoke excellent English we could have fallen on his neck. He, good soul did the rest of our shopping for us, even letting us rest like hunted animals for a while in his little parlor. But when we got out again our escort had not dispersed; on the contrary, it had been considerably augmented, and once more we stepped bravely out, trying to appear perfectly at ease.

On the pavements stood the grown-ups placidly smoking their pipes, leaning up against walls to have a more comfortable view of us. Out army sang to us now, and two or three ran before capering and jigging like Davids before the Ark. The singing was the last straw. It had been bad enough to hear the clattering of clogs, the chuckling and the laughing, but the singing, the ever-swelling volume of shrill voices, was more than we could bear. I remembered with agony that my trousers were still seatless, and hoped my coat hid the fact. One little boy, more daring that the rest, poked William in the back. They hopped around and about us like performing fleas. To show signs of resentment would have been useless, and would have been met by worse on their part, and we had to carry out our retreat to the dinghy with as much dignity as we might. I never was so glad to get into a boat in my life, and a few feet from the quay we lay on our oars and counted them. There were forty-nine!

The passage from Tholen to Philipland through the narrow creek was the most amusing of any. Our chart gave the water shed as drying six feet at low water, so that we had none too much to spare. However, we started from Tholen at about two hours flood to do the best we could. It rained a little, and William got Oswald to haul him up in the bosun's seat to Alterlie's mast head, were he sat under an umbrella and gave directions as to where we should find the best water. Mave-Rhoe followed and it simply convulsed me to see the utter surprise of occasional people on the bank at the sight of us.

The watershed of the creek is near a place called Oud Vosmeer (which Oswald, with his cockney wit, continually referred to as "old has-been"), but we ran aground three times before we got there. It was plain sailing enough up to Nieu Vosmeer Ferry, but after that the channel is extremely narrow and curves almost in a semi-circle. One should keep to the left-hand side, and literally not more than ten feet away from the mud, which is evidently very steep, too; one might, I think, go even closer than that. Our chart (a cruising club one of some years ago) must have been inaccurate to that particular creek, for although it was only four hour's flood we found plenty of water, and it was not until we were over the watershed and the entrance (which is buoyed) was in sight that our troubles began. The channel wound about all over the place, and Oswald and William (he had by this time to abandon his bosun's chair and umbrella to help with Alterlie) found their hands full. Fortunately, as the tide was still making, running aground was not such a desperate business, but I don't think I've ever had such a hard hour's work in my life. Between us we must have struck a dozen times. If Alterlie was sailing Mave-Rhoe was on the mud, and sometimes we were both on together. We had to use our boat hooks as a blind man uses his stick--prod, prod, the whole time. Not only did the channel curve but it seemed to wind back alongside itself like a river in Cambridgeshire, and one had no sooner pushed off one side and hauled one's mainsail in to get away from it than one was fast on the other. However, we reached the first buoy at last, with the feelings of an intoxicated person reaching a post after the perils of the open road, and after that the channels through the sands are all buoyed up to St. Philipland. It being Sunday evening, the entire population was taking its ease on the sea wall, and at the sight of us set up a hubbub and commotion that made our friends at Tholen seem lackadaisical and lukewarm. But we had no intention of providing another raree show, and brought up off the sea wall with the fixed intention of staying there. We did venture ashore after dark and had a look at the town, but it was an uninteresting place, and, as far as we could see, quite modern.

From St. Philipland we jogged on to Wilhelmstadt, a little fortified town with a rather picturesque harbor. We had had enough of harbors for the moment, however, and chose to lie out in the tideway, not a good anchorage in bad weather, but tolerable on a quiet night. This was the furthest point on our outward journey, and on the morrow attempted a passage back to Veere. It was a fine sail, windward work for the greater part of the way in a whole mainsail breeze, but Fortune had evidently not forgiven my remark about the lack of incident, and about half way through my windward shroud suddenly went. Fortunately, my windward runner was well set up, else the mast must assuredly have gone--and, with the help of a tackle, we did in some sort of fashion repair the mishap, and got going again. But through the delay we lost our tide and had to content ourselves with making Zerixee Harbour against the strong flood. Just before we got in, two English barges, the largest, I think, that I have ever seen, came foaming in from seaward with the wind dead behind them. Every stitch was set, and beside the under-canvassed schuyts and botters that we had grown accustomed to, their spread of sail seemed enormous. Perilous looking craft the Dutchmen must have thought them.

At Zerixee we had no choice but to lie along the quay (to our utter discomfiture, as you shall hear) and brought up before the usual stolid yet fascinated audience.

While we were debating among ourselves as to how on earth we should ask for wire rope, a pleasant-spoken person on the quay addressed us in tolerable English. Fondly imagining him (quite incorrectly) to be an angel in disguise, we put ourselves in his hands and told him of our needs. He seemed to understand perfectly what we wanted, and while we perambulated the streets of Zerixee, he carried on a more or less intelligent conversation. Judge then, of out utter surprise when he finally escorted us into a boy's outfitters! To this day I cannot conceive what maggot was in his brain, for his first essay having been unsuccessful, he straight away conducted us to am ironmonger's shop, where we found what we wanted. I might add that that new shroud was eventually fitted at Burnam-on-Crouch, so we might as well have saved ourselves and him the trouble. And now comes the devilish perverseness of this old person's character. We were moored alongside the quay, as I say, Alterlie inside, Mave-Rhoe outside. There was quite a largish steam yacht but a few yards away, and various craft quite near us, so that any doubt as to drying out never entered our minds. Our old man having fussed about us and shown off his English before his friends, finally sold us some cherries and departed, so that after dinner we turned in without a qualm.

On the pavements stood the grown-ups placidly smoking their pipes, leaning up against walls to have a more comfortable view of us. Out army sang to us now, and two or three ran before capering and jigging like Davids before the Ark. The singing was the last straw. It had been bad enough to hear the clattering of clogs, the chuckling and the laughing, but the singing, the ever-swelling volume of shrill voices, was more than we could bear. I remembered with agony that my trousers were still seatless, and hoped my coat hid the fact. One little boy, more daring that the rest, poked William in the back. They hopped around and about us like performing fleas. To show signs of resentment would have been useless, and would have been met by worse on their part, and we had to carry out our retreat to the dinghy with as much dignity as we might. I never was so glad to get into a boat in my life, and a few feet from the quay we lay on our oars and counted them. There were forty-nine!

The passage from Tholen to Philipland through the narrow creek was the most amusing of any. Our chart gave the water shed as drying six feet at low water, so that we had none too much to spare. However, we started from Tholen at about two hours flood to do the best we could. It rained a little, and William got Oswald to haul him up in the bosun's seat to Alterlie's mast head, were he sat under an umbrella and gave directions as to where we should find the best water. Mave-Rhoe followed and it simply convulsed me to see the utter surprise of occasional people on the bank at the sight of us.

The watershed of the creek is near a place called Oud Vosmeer (which Oswald, with his cockney wit, continually referred to as "old has-been"), but we ran aground three times before we got there. It was plain sailing enough up to Nieu Vosmeer Ferry, but after that the channel is extremely narrow and curves almost in a semi-circle. One should keep to the left-hand side, and literally not more than ten feet away from the mud, which is evidently very steep, too; one might, I think, go even closer than that. Our chart (a cruising club one of some years ago) must have been inaccurate to that particular creek, for although it was only four hour's flood we found plenty of water, and it was not until we were over the watershed and the entrance (which is buoyed) was in sight that our troubles began. The channel wound about all over the place, and Oswald and William (he had by this time to abandon his bosun's chair and umbrella to help with Alterlie) found their hands full. Fortunately, as the tide was still making, running aground was not such a desperate business, but I don't think I've ever had such a hard hour's work in my life. Between us we must have struck a dozen times. If Alterlie was sailing Mave-Rhoe was on the mud, and sometimes we were both on together. We had to use our boat hooks as a blind man uses his stick--prod, prod, the whole time. Not only did the channel curve but it seemed to wind back alongside itself like a river in Cambridgeshire, and one had no sooner pushed off one side and hauled one's mainsail in to get away from it than one was fast on the other. However, we reached the first buoy at last, with the feelings of an intoxicated person reaching a post after the perils of the open road, and after that the channels through the sands are all buoyed up to St. Philipland. It being Sunday evening, the entire population was taking its ease on the sea wall, and at the sight of us set up a hubbub and commotion that made our friends at Tholen seem lackadaisical and lukewarm. But we had no intention of providing another raree show, and brought up off the sea wall with the fixed intention of staying there. We did venture ashore after dark and had a look at the town, but it was an uninteresting place, and, as far as we could see, quite modern.

From St. Philipland we jogged on to Wilhelmstadt, a little fortified town with a rather picturesque harbor. We had had enough of harbors for the moment, however, and chose to lie out in the tideway, not a good anchorage in bad weather, but tolerable on a quiet night. This was the furthest point on our outward journey, and on the morrow attempted a passage back to Veere. It was a fine sail, windward work for the greater part of the way in a whole mainsail breeze, but Fortune had evidently not forgiven my remark about the lack of incident, and about half way through my windward shroud suddenly went. Fortunately, my windward runner was well set up, else the mast must assuredly have gone--and, with the help of a tackle, we did in some sort of fashion repair the mishap, and got going again. But through the delay we lost our tide and had to content ourselves with making Zerixee Harbour against the strong flood. Just before we got in, two English barges, the largest, I think, that I have ever seen, came foaming in from seaward with the wind dead behind them. Every stitch was set, and beside the under-canvassed schuyts and botters that we had grown accustomed to, their spread of sail seemed enormous. Perilous looking craft the Dutchmen must have thought them.

At Zerixee we had no choice but to lie along the quay (to our utter discomfiture, as you shall hear) and brought up before the usual stolid yet fascinated audience.

While we were debating among ourselves as to how on earth we should ask for wire rope, a pleasant-spoken person on the quay addressed us in tolerable English. Fondly imagining him (quite incorrectly) to be an angel in disguise, we put ourselves in his hands and told him of our needs. He seemed to understand perfectly what we wanted, and while we perambulated the streets of Zerixee, he carried on a more or less intelligent conversation. Judge then, of out utter surprise when he finally escorted us into a boy's outfitters! To this day I cannot conceive what maggot was in his brain, for his first essay having been unsuccessful, he straight away conducted us to am ironmonger's shop, where we found what we wanted. I might add that that new shroud was eventually fitted at Burnam-on-Crouch, so we might as well have saved ourselves and him the trouble. And now comes the devilish perverseness of this old person's character. We were moored alongside the quay, as I say, Alterlie inside, Mave-Rhoe outside. There was quite a largish steam yacht but a few yards away, and various craft quite near us, so that any doubt as to drying out never entered our minds. Our old man having fussed about us and shown off his English before his friends, finally sold us some cherries and departed, so that after dinner we turned in without a qualm.

The Three Fat Girls of Zerixee.

Alas! alas! for that unfortunate remark of mine. In the middle of the night I was awakened by a sudden lurch on Mave-Rhoe's part, and a thud as if the whole quayside had fallen on to her. I dived out of my bunk and cabin at just the same moment as William, and for a brief moment stared at him in sleepy stupefaction. Then, "Good Lord, William," I said "Alterlie's falling on top of Mave-Rhoe!" And so she was! The reason was simple enough. We were drying out, and the mud being very steep too, Alterlie had grounded first, while Mave-Rhoe (being outside) was still afloat.

The sudden lurch was caused by Alterlie's stern-warp suddenly pulling out the cleat to which it was made fast, and part of the well-coaming. For the next few minutes we were pretty busy, and William and Oswald hurriedly ran a line from Alterlie's mast-head to a bollard on the quay. Fortunately she had listed but a little way, and they were able to haul her back to the perpendicular, while I shoved Mave-Rhoe further out into the channel. As we worked we cursed the old man, cursed him and all his works, and it was not till all was safe that we were able to appreciate the humour of the business. However, no harm was done except that Alterlie's side looked like some large animal had taken a bite out of it, and presently we turned in. When our friend eventually came to take a look he said complacently, "Ha--you took--a--devil--of--a--list?" a remark so entirely callous that we had no retort. We were much annoyed that morning, I remember, by three stout girls, who came and watched us preparing our breakfast and our toilet. They tittered and giggled, and giggled and tittered, and encouraged two little boys to titter too. We were pretty well used to frank scrutiny by this time, but there was about those girls something particularly exasperating. We finally got rid of them by puffing out our cheeks until they ached, pointing to the stout girls on the quay and grinning at one another, a method that was effective as it was ungallant.

"You took the Devil of a list, eh?"